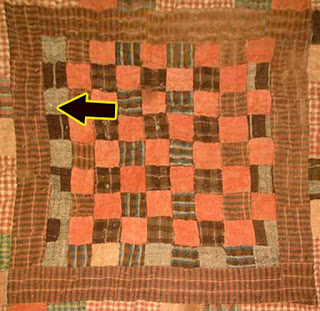

Quilt attributed to Ann Sloan Knox

North Carolina Museum of History

Last week I discussed this quilt of plaids, stripes and butternut---coarse fabrics commonly called linsey and jeans. My first thought when I saw the details was that the fabrics were homespun and home woven as the donors suggested---clothing worn by Ann's sons in the Confederate Army, perhaps spun and woven by Ann herself during the war.

But a little research into Ann Knox's life reveals she was a wealthy woman who was unlikely to have spent her time at a spinning wheel. Before the war husband Samuel Buie Knox was worth over $200,000. The 1860 census lists him personally as having a dozen slaves. When he died in 1875 he left hundreds of acres in various plantations in an estate worth $7,000, a diminished fortune, but still substantial.

Lucindy Jurdon, former slave, shows

her mother's spinning wheel to a

WPA interviewer in Georgia in 1938

"My mammy was a fine weaver..."

If any domestic fabric production took place on the Knox properties before Emancipation, the spinners and weavers were probably the slaves. The origins of the fabric and of the patchwork quilt raise many questions.

An alternative view of the quilt's fabrics is that the various cottons, wools and mixed materials were factory-woven at local mills in the Steele Creek community along the Catawba River.

The Catawba River runs near Steele Creek on the

North Carolina/South Carolina border.

William Henry Neel's Steele Creek Cotton Mill was a grist mill converted to cotton production in the 1850s. The neighborhood mill did not produce a lot of cloth, but some of it may be in this quilt.

The small Schenck Mill began cotton production in

1813, the first cotton mill in North Carolina.

In 1848 the Rock Island Woolen Mill, named for Rock Island shoal in the Catawba, was founded.

In 1849 the machines produced about 200 yards of cloth per day. The following year's census records 53 people employed there, a relatively large enterprise.

In 1852, the mill advertised cassimeres, tweed, jeans and kersey. These were not fine wool broadcloths, fancy delaines or crepes but cheaper fabrics woven from coarse yarns.

A reproduction cassimere wool

Cassimere weave

"a cross between the basket weave and a twill... "

Four patch of finer printed wools known as delaine and challis,

probably imported from Europe

The types of cloth described differ mainly in type of weave and weight.

The fabric in the center of Ann Knox's quilt

looks much like the reproduction

"Brown Jeans Cloth"

sold today by William Booth Drapers.

The Rock Island Mill seems to have thrived in Steele Creek until the Civil War began in 1861. Operations then moved a few miles into the city of Charlotte, probably to ramp up production for Confederate uniforms. As the War dragged on higher quality fabric was harder to find. The fabrics in the medallion quilt may have been scraps from Ann Knox's wartime family clothing, stitched from locally purchased cloth.

Post-war production at Rock Island continued in similar style. An 1869 description of the mill's Charlotte products:

"One thousand to twelve hundred yards of cassimeres per day...The goods are from all wool cassimeres with double and twisted all wool warps, fit to adorn a Broadway dandy, down to the strong, heavy, durable jeans, so much liked by our own people, and so cheap as to be within the reach of the poorest."So while the fabrics in the Knox quilt may have been cut from the shirts Ann's sons wore before their deaths near war's end, the fabric might very well have been factory cloth from the local mill.

Linsey quilt, a nine-patch set with madder-dyed wool strips

similar to fabric in Ann Knox's center.

The romanticism of "homespun" often embellishes the view of donors. As Clement Anselm Evans wrote in his 1899 Confederate Military History:

"Homemade woolens had a sanctity in my eyes as true emblems of honesty and innocence."

Homewoven or factory woven?

The results would look the same, no matter how mechanized

the small pre-War factory

Steele Creek Presbyterian Church today

Locally produced fabrics from small mills/factories are also worth saving as quilts and in museums, but the romance of "innocent homespun" tends to override an accurate history of successful industry.

The Spinner 1880,

Painting by Thomas Wilmer Dewing

Lewis Hine, "Warper at his Machine,"

Mill in Newton, NC, 1908

Library of Congress

Account of a fire at the old Rock Island Woolen Factory building.

Screen shot from American Memory

from the Library of Congress.

The question of who actually made the quilt might also be contested. It's time to look at these "honest homespun" quilts in an honest historical context.

Read about the cotton mills of Mecklenburg County here:

http://www.cmhpf.org/essays/cottonmills.html

http://www.cmhpf.org/essays/cottonmills.html

3 comments:

Thank you for investigating this quilt's story. It's always disturbing to see US history presented without mention of the slaves who were present and very busy contributing to our economy and the Southern lifestyle. It was also enlightening to learn that there were small mills in the South producing this grade of fabric. I'd heard of Alamance (NC) plaid but didn't know there were other mills as well.

I enjoyed your in depth search for accuracy concerning this quilt. Quilts are so much more than just a covering for a bed.

Post a Comment