Block #1 Hospital Sketches

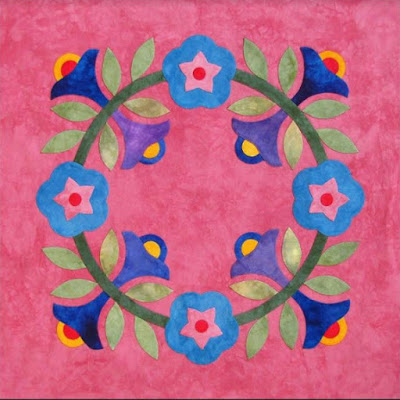

Periwinkle Wreath by Becky Brown

We begin the Hospital Sketches applique sampler with Periwinkle Wreath, recalling the Union Hotel Hospital in Georgetown, Washington City.

Union Hotel Hospital

During the Civil War

Hannah Anderson Chandler Ropes (1809-1863) was the matron

at the makeshift hospital.

Matrons were more housekeepers than medical assistants. Hannah would have been in charge of the kitchen, the laundry and the female nurses, although she certainly worked one on one with patients. Hannah was in her early fifties when she arrived in summer, 1862, readying the building to take wounded from the Seven Days campaign near Richmond, Virginia.

Louisa called it the Hurley-Burley House Hospital

Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888)

Louisa published her Hospital Sketches under the pen name "Trib Periwinkle,"

inspiration for our first floral block.

Periwinkle Wreath by Bettina Havig

In a letter to another veteran of the Union Hospital, Louisa wrote:

"My ward is the lower one & I parade that region like a stout brown ghost from six in the morning till nine at night haunting & haunted for when not doing something I am endeavoring to decide what comes next being sure some body is in need of my maternal fussing."

Trib Periwinkle recalled her dwelling at the Hurley Burley House:

"The windows suffered compound fractures...narrow iron beds, spread with thin mattresses like plasters, furnished with pillows in the last stages of consumption... A mirror (let us be elegant!) of the dimensions of a muffin and about as reflective."

What a writer she was!

Patients in a ward built as a hospital with emphasis on

ventilation to keep air-borne diseases from spreading.

The Union Hospital had few windows.

The wards were no better: “A more perfect pestilence-box than this house I never saw.”

An extremely rosy picture, supposedly of a ward at the Union Hospital---

Jenny Lind spool beds for everyone.

Armies were desperate for spaces to care for the overwhelming number of sick and wounded. Louisa arrived soon after the Battle of Fredericksburg. Her patients died of trauma, infection and field amputations but also of measles, pneumonia, typhoid and dysentery.

Illustration of Louisa in the ward from

a 20th-century edition of Hospital Sketches

"Miss Alcott and I worked together over four dying men and saved all but one....but whether [due to] our sympathy for the poor fellows or we took cold, I know not, but we both have pneumonia and have suffered terribly."Back in Concord Louisa's letters stopped. Young neighbor Julian Hawthorne remembered:

"A hush of suspense fell upon us. Then came an official dispatch from the front. Miss LA had caught the fever and was being invalided home....on my way to and from school I would call at the house for news and go away heavy hearted. Mrs. Alcott would shake her head, pale and sad, and [Sister] Abby's eyelids were red and her smiles gone."Hannah notified Bronson Alcott to come to Washington. On January 20th, the day Louisa's father arrived, Hannah Ropes died with her daughter Alice at hand.

Orchard House, the Alcott home in Concord during the Civil War.

From the Orchard House Museum

The Block

Periwinkle Wreath by Janet Perkins

Janet and Bettina are each using a single monochrome print

for their backgrounds.

Wreaths with flowers on the north/south axis and buds on the diagonals

are one of the most popular of 19th century applique designs.

See a post about the history of appliqued wreath blocks here:

Here we've changed the traditional rose to a flower based on five,

a purple periwinkle

To Print:

Create a word file or a new empty JPG file. Click on the image above.

Right click on it and save it to your file.

Print that file. Be sure the square is about 1" in size.

For the background cut a square 18-1/2"

Add seam allowances to the pattern pieces if you are doing traditional applique

Me, Barbara, I'm using reproduction calicoes from my stash and my purple box is pretty empty.

But periwinkles come in pink too. The backgrounds are pieced a la Piece O'Cake applique. I cut 9-1/2" squares of light prints and pieced them randomly together. Ouch! The red solid is bleeding.

Addition

Becky is doing some addition---here she's filled the empty space in the middle of the wreath with another floral. She's designed a class in how to make applique your own and addition is a theme.

Subtraction

Sprouts #1

Each month you'll get a Sprouts design, an adaptation of the traditional pattern, using just a few of the elements from the more complex pattern, sized to fit 8-1/2" finished backgrounds.

For Sprouts #1:

- Cut a 9" square

- Cut 1 each of pieces A, B, C, D, E & G.

- And two leaves F.

- You'll need stems for the monthly sprouts so you might want to make some 1/2 finished bias ahead of time. You'll use about 5-6" each month.

Denniele Bohannon's #1 Periwinkle Sprout

UPDATE: Denniele reminds me her blocks are 9-1/2" finished.

Gives her more room for a longer stem.

She's using the aqua solid as a background for all her Sprouts

and pastel prints for the raw-edge, machine applique.

Blue dots are a recurring theme.

After the War:

Louisa's few weeks at the Union Hospital affected her for the rest of her life. We know her, of course, as the successful author of Little Women, in which she writes unforgettably of Marmee fetching her soldier husband home to Concord, an echo of Louisa and her father's journey from the Union Hotel Hospital.

Tribulation Periwinkle's coat of arms from

Hospital Sketches

Although rich and lionized she never enjoyed consistent health again until her death at the age of 55. Reading her letters and other accounts one gets the feeling she suffered a form of post traumatic stress syndrome after her six weeks at the Union Hospital. Anxiety and depression were never far away again. She believed she'd been poisoned permanently by the mercury treatment administered for her Union Hospital illness. She suffered from joint pain and exhaustion, perhaps a serious autoimmune disorder like arthritis, thyroid disorder or lupus; perhaps a cancer like lymphoma or leukemia.

Louisa May Alcott sat for American portrait

painter George Healy while living in Rome in 1870

when she was not yet 40 years old.

Spending six weeks in the Union Hotel Hospital was a wonderful if terrible experience for Louisa. She asserted her independence, obtained real life experience for her writing and became a publishing star with Hospital Sketches.

Elizabeth Tobias Dixon, Paris Indiana

Indiana project & the Quilt Index.

Addition---see how many buds you can fit in one wreath.

Subtraction ---No buds, 12 leaves.

Quilt dated 1863, Addie Little on a label.

Collection of the Museum at Michigan State University

Six of the 16 blocks are wreaths, indicating their importance

in album iconography.

Extra Reading:

Here's an online version of Louisa May Alcott's Hospital Sketches:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3837/3837-h/3837-h.htm

See a preview here:

https://books.google.com/books?id=AAyPxFq3SiIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=hannah+ropes+civil+war+nurse&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjUrOWUpsTZAhUJQq0KHXG0BQsQ6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=hannah%20ropes%20civil%20war%20nurse&f=false

Louisa's unpublished letter to Hannah Stevenson from the Curtis Stevenson Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society.