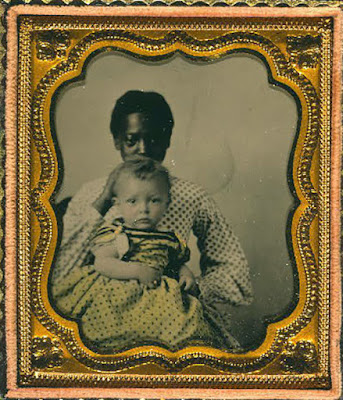

Ambrotype, Unknown woman and baby about 1855

Library of Congress

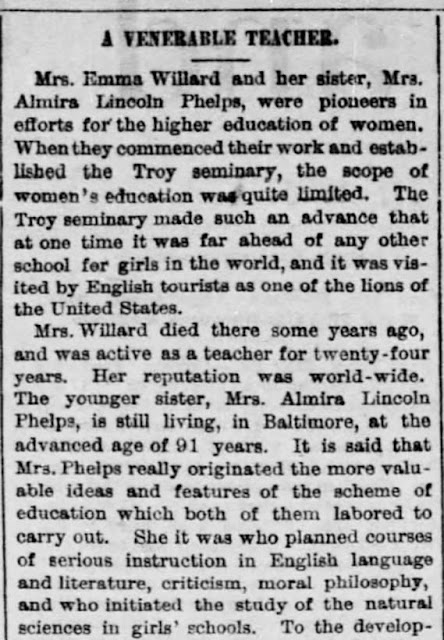

At the Civil War's beginning Lucy Lewis was one of about 14,000 enslaved people in the city of New Orleans. She was a domestic servant who lived in the home of Solomon P. Solomon on Hercules Street (renamed Rampart Street.)

Historic New Orleans Collection

This 1895 photo of a rare snowstorm shows the kind of

elegant houses one might see on North Rampart Street

35 years earlier.

Solomon Phineas Solomon (1815-1874)

A New Orleans merchant when the war began

he traveled to Virginia to open a sutlery, a

store for Confederate soldiers.

Lucy was born in South Carolina as was Solomon and his wife Emma. Perhaps the Solomons brought a young Lucy with them when they moved to New Orleans soon after their marriage.

Clara Solomon ( 1845-1907)

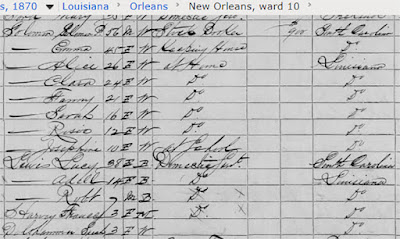

The 1860 census in July lists the free people on Hercules Street, omitting Lucy and Dell.

Solomon, a Com Merchant, is a Commission Merchant, a wholesaler,

worth only $1,000 (and that includes Lucy and Dell's value.)

Lucy's duties were typical of a housekeeper---cleaning, cooking, marketing and answering the door. She ran errands and got up first, waking the girls early with a shake and a word or two (or more if they didn't want to get up.) She dressed the younger children and dressed the older girls' hair.

Frances (Fanny) Solomon (1847-1881) in the 1870s when

elaborate hair styles (often incorporating switches and

false hair) were the rage.

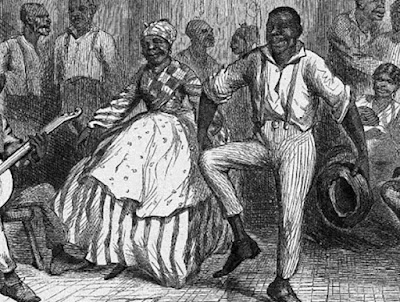

Hair braiding was a common daily occupation for Lucy and the older girls. Fanny's rather elaborate look above is typical of national fashion in the 1870s but apparently girls in New Orleans sported a version the style during the war too. Clara, never satisfied with her appearance, relied on Lucy to "comb" her. "How dependent I am. Unable to look nice, if L. does not 'have a hand' in my toilette."

Yale University Library

Unknown woman and child

Childcare was another duty shared by all. Josephine was a year old as the war began and she and her tantrums kept Clara and Dell busy. A hired girl Ellen Deegan about 11 years old came in daily to manage Josie. Ellen was young and not very reliable so how much assistance she offered Lucy or sister Clara is questionable.

With father gone, hoping to make his fortune, the women were suddenly poor in the fall of 1861. Until cash arrived from him they took in sewing, constructing "drawers" for the Confederate Army. Sixteen-year-old Clara reported that a local merchant had received an order for 600. Seamstresses earned $1.25 per dozen.

Unknown woman and machine

Clara: "The machine has been useless as it has the greatest kind of fits."

Lucy seems to have taken no part in the sewing. Her housekeeping and child care labors gave the Solomons time to sew the underwear, which "are not much work but Ma only made three pair, as Josie was was so very bad, we found it impossible to sew. In ordinary times we could make about 10 pairs." Ellen's mother Bridget Deegan also sewed drawers but had no machine so earned less per hour than the Solomons.

Clara and her mother Emma seem to have been the chief seamstresses. Despite the machine's "fits" Clara mastered it and spent the rest of the war contentedly sewing utilitarian family clothing and fashion for herself, Alice and Fanny.

Lucy had a life away from the family with daughter Adelle as primary evidence. Clara noted that Lucy "as usual went out" after bidding her good night. By the time Clara's diary ended in summer 1862 Lucy may have again been pregnant with son Robert born in 1863.

In the fall of 1861 Lucy's friend Jacksine brought a gift from a man named Solomon, living in Covington on the other side of Lake Pontchartrain. He was "crazy to see Lucy; he thinks the world of her." But we do not hear of him again.

Union troops remove the state flag at City Hall 1862

The Union Army occupied New Orleans in 1862. Although "They say they do not intend to interfere with slavery" the Solomons worried about Lucy's loyalty. "Ma is quite troubled about her, as so many (her acquaintances some) have run away and sought the protection of the Yankees."

Lucy must have stayed throughout the Union occupation and into the next decade as she and her two children remained with the Solomon family for the 1870 census.

The Solomons, troublesome as they were, represented the only family Lucy had ever known. Lucy disappears from the records after this census.

1880 Census, Hot Springs, Arkansas

After the war Clara married twice, the second time to George Lawrence, a Pennsylvania veteran of the Union Army. They lived for a time in Hot Springs, Arkansas, next door to Lucy's daughter Adele and baby James, Lucy' grandson whose father was born in Tennessee.

1883 Hot Springs Directory

Solomon, Clara. The Civil War Diary of Clara Solomon. Edited by Elliot Ashkenazi. Baton

Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press. 1995.

.jpg)