Georgann Eglinksi

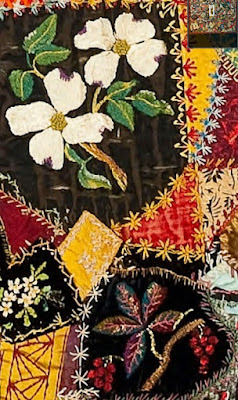

Block # 6 Canada Lily for Mary Milburn (Louisa Jones)

Mary Millburn/Louisa F. Jones from William Still's book

The Underground Railroad

Fashion and age in her portrait look more like 1870, the time

of the book's publication rather than the time of her escape in 1858.

Canada Lily remembers Mary Millburn who planned to run all the way to Canada but liked Boston so much she stayed. Mary changed her name to Louisa F. Jones, making her difficult to track (as someone who changed her name to Jones undoubtedly hoped.) William Still wrote a bit about her, telling us she'd been a slave to two women named Chapman in southern Virginia down by Norfolk who raised her to be ladylike in rather gentle circumstances. Yet slavery "galled her spirit" and she "was determined to escape."

"She was able to contact members of the Underground Railroad."

Her method was fairly common in Still's accounts. She booked secret passage on a steamship to Philadelphia.

Sympathetic captains risked much to hide a fugitive. Captain Daniel Drayton was caught with 75 fugitives on his ship in 1848 and sent to jail but President Millard Fillmore pardoned him. Others, like

human traffickers today, profited hugely by ferrying passengers to Northern ports. Although John Atkinson did not indicate who paid his ticket or if he was even charged a fee, he told Still about traveling as "a private passenger on one of the Richmond steamers smuggled by the boat's steward." A profiteer or a friend of the slave?

Escaping by ship

A sudden summons in the spring of 1858 told Mary/Louisa to dress in men's clothes (disguise often noted probably because cross dressing showed the perceived indignities enslaved women were forced to endure.)

Still also told Maria Weems's story of adopting men's clothing.

Mary/Louisa's clandestine voyage may have begun similarly to a report by another Virginia fugitive that year who was advised to "come down to the steamer about dark and if all is right you will see the Underground Rail Road agent come out with some ashes as a signal."

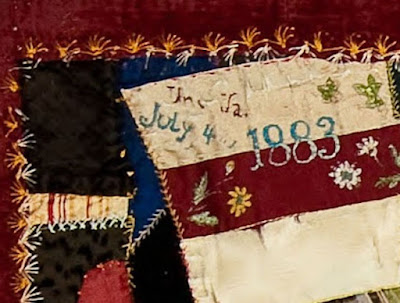

1840-1860

At the dock Mary/Louisa was stowed away in a wooden crate secreted from the police officers making their "usual search" for suspicious looking African-American passengers.

A runaway from Manchester, Virginia who sometimes

called herself Mary, March, 1858.

Once uncrated in Philadelphia (I doubt she stayed in that crate on the voyage) she found William Still and the Vigilance Committee who sent her on to New York City where she was given a letter of introduction to Boston's William Lloyd Garrison, the famous publisher of The Liberator.

"I found him and his lady both to be very clever. I stopped with them the first day of my arrival here, since that Time I have been living with Mrs. [Susan Howe] Hillard. I have met with so many of my acquaintances here, that I all most imagine myself to be in the old country."

Mrs. Hillard's House

62 Pinckney Street from Google Earth

Susan Tracy Howe Hillard (1808-1879) was a

remarkable woman about whom we wish we knew more.

Thanking William Still for his recent help Mary/Louisa wrote she had not gone to Canada as planned but stayed in Boston (she seemed to be enjoying it and she did well there.) Characterizing her as industrious Still wrote she found "a situation immediately." By the early 1870s when composing his book he reported she was a fashionable dressmaker doing a good business.

Ads for Boston dressmakers in the 1870s

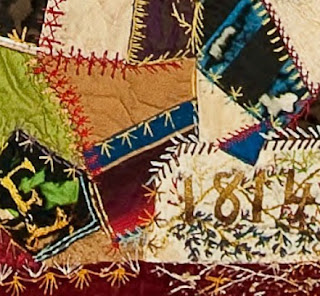

The Block

blocks dated 1846 when blue and buff stripes were all the rage for women's dresses.

Portrait of Vrylena Blanchard Frothingham (1812-1890)

in just such a dress with son Thomas Goddard,

Massachusetts, about 1845

Historic New England collection

Mary/Louisa and the Canada Lily (Lilium canadense) are both Virginia natives.

The wildflower blooms in clusters.

Print this on an 8-1/2" x 11" sheet. See the inch square for scale.

You might prefer to piece the stars and add a frame to make them the

right size. Then add the applique.

Becky Brown's adaptation

A cluster of four.

Further Reading

We don't often think of ships ferrying runaways North. Read Timothy D. Walker's Sailing to Freedom: Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad from the University of Massachusetts Press.