First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln in her late forties at

a White House event.

https://www.raegunramblings.com/

Mary Lincoln was a shopping addict and found entertainment and peace in choosing material for White House interiors and her own wardrobe during the Civil War.

Mary Ann Todd Lincoln (1818-1882)

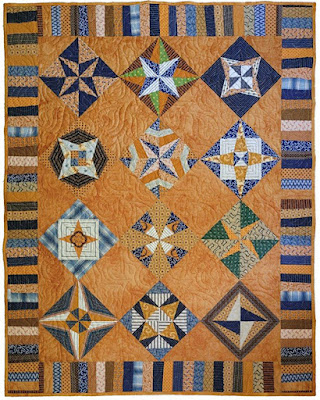

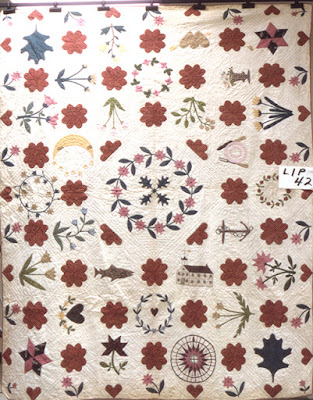

The times required yards and yards of fabric for bell-shaped skirts and Mary felt it was her obligation to look well-turned out in her White House years. She liked shopping in New York. Congress allotted $20,000 for refurbishing the Executive Mansion over 4 years. She overspent that budget by $6,000 the first year spending what would be nearly $500,000 today on drapes, carpets, furniture, etc.

Journalist "Grace Greenwood's" summary of Mary Lincoln in 1895,

a decade after Mary's death.

1864 ad in the New York Herald

Mary put her purchases for her clothing on her personal tab, running up about the same amount in debt to department and dry goods stores and milliners such as Madame Harris on Broadway. $500,000!!!

Mourning bonnet worn after son Willie's death in 1862

She was fussy if not downright difficult.

"I am in need of a mourning bonnet---which must be exceedingly plain and genteel....I want the crape to be the finest jet black English crape----I want it got up with great taste and gentility." May, 1862

Her husband knew little about this outrageous debt but people looking for Presidential favors did.

She and her skillful Modiste Elizabeth Keckly

made good use of some of the luxurious fabrics

but much yardage was never made up into clothing.

After her husband was assassinated in 1865 Mary left the White House for Chicago with about 60 trunks and boxes full of belongings. She found shopping a balm for grief. What was a compulsive shopping problem became a hoarding disorder.

She was never satisfied in one place very long. She bought a Chicago house at what is now 1238 West Washington Boulevard, east of Union Park, and then after a year rented it out as she traveled. She never returned to live in the house but continued to store trunks and boxes there.

Ruins of Chicago, 1871

She did not mention this catastrophe in her surviving letters although

she was in Chicago at the time.

Some of the trunks stayed in that house, which survived the fire; some went to son Robert and his new wife Mary Harlan Lincoln. Letters to her daughter-in-law from Europe, indicate she had a mental inventory of every piece of fabric in the boxes she'd left behind.

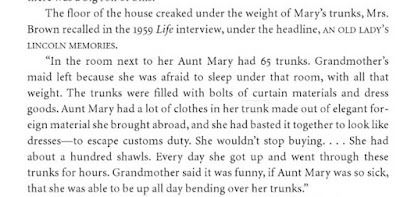

The older Mary Lincoln left trunks in Chicago but brought many with her on extended visits to Europe. Being both a hoarder and a woman never content long in one spot is a bad combination of disorders.

https://books.google.com/books?id=4EUEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA17&dq=February%209%201959%20Life&pg=PA48#v=onepage&q&f=false

"In the box---by the front door upstairs is a box of woolens 2---elegant sofa cusions (sic)"

"If you have need of any narrow thread lace---which you will certainly require----you will find some among my lace----which has never been washed

Mary Harlan Lincoln (1846-1937)

seems to have had the Mother-in-Law from Hell.

Mary's demands and advice got so bad Robert and

his wife separated for a year.

Mary also found solace in spiritualism,

which connected her to her deceased

husband and three sons. Her losses

were great; her reactions dramatic.

In 1875, after ten years as a widow, Mary's only surviving child Robert committed her to an insane asylum. She was hoarding a good deal of cash and redeemable securities by pinning and sewing them to her undergarments. Robert believed declaring her insane was the only way to protect her finances under his management. Once again her possessions were in the forefront of her thoughts. She demanded the return of gifts she'd given Robert and his wife, which went back into the trunks.

Elizabeth & Ninian Edwards's house in Springfield, Illinois

She spent the last few years in the care of her generous sister Elizabeth Edwards who gave her a home in Springfield. Mary spent her days sifting through her fabrics---dress silks and laces a widow could never wear; draperies for houses she did not live in.

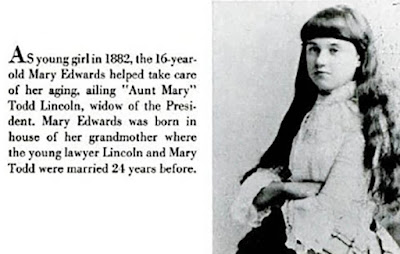

As late as 1959 people were still reporting on Mary Lincoln's eccentricities.

Above a Life Magazine interview with

a niece Mary Edwards Brown.