In July, 1855 William Still at the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee offices received a hand-delivered note:

Still ran to get help from fellow Committee member Passmore Williamson. One of the group's prime duties "when hearing of slaves brought to [Pennsylvania] was to immediately inform such persons that they were not fugitives...were entitled to their freedom without another moment's service [and] advice of counsel without charge."

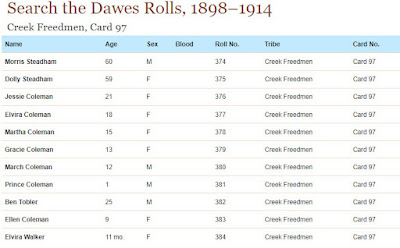

Jane Johnson was the Washington-born slave of John Hill Wheeler, a North Carolina politician living in Washington City. He had purchased her about 1853 with sons Daniel, about 10, & 9-year-old Isaiah. (Her previous owner sold another son.) The Wheelers and Johnsons had taken the train cars from Washington and spent some time with the parents of Wheeler's wife Ellen, the Thomas Sullys.

"Slave-holders fully understood the law...Consequently they avoided bringing slaves beyond Mason & Dixon's line....But some slave-holders were...too arrogant to take heed. [Wheeler] received a terrible shock at the hands of the Committee."

As the ferry was loading Williamson found:

"Jane and her children seated upon the upper deck [inquiring] 'You are the person I am looking for, I presume.' Mr. Wheeler, who was sitting on the same bench, three or four feet from her, asked what Mr. Williamson wanted with him. The answer was, 'Nothing, my business is entirely with this woman.' Amid repeated interruptions from Mr. Wheeler, Mr. Williamson calmly explained to Jane that she was free under the laws of Pennsylvania, and could either go with Mr. Wheeler, or enjoy her freedom by going on shore."

"Wheeler...clasped her tightly round the body. Mr. Williamson pulled him back and held him till she was out of danger from his grasp. Jane moved steadily forward towards the stairway leading to the lower deck. It was at the head of the stairway, if we may believe Mr. Wheeler, that he was seized by two colored men and threatened by one of them; but the most careful and repeated examination of witnesses has failed to elicit any testimony to a threat except one made on the lower deck. She was led down the stairs of the boat and her children picked up and carried after her; one of them cried vociferously. She and her children were conducted ashore, and put into a carriage, and, amid the huzzas of the spectators, were driven off to a place of safety."Some accounts say that place of safety was Letitia and William Still's boarding house. Abigail Goodwin, a New Jersey "agent" worried about Jane.

"You will take good care of Jane Johnson I hope, and not let her get kidnapped back to Slavery. Is it safe for her to remain in your city....do try to impress her with the necessity of being very cautious and careful against deceivers, pretended friends. She had better be off to Canada pretty soon."

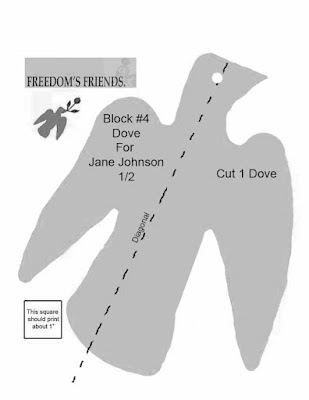

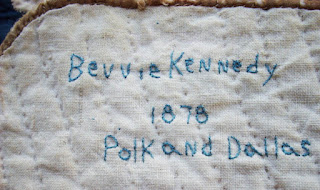

Now the model makers thought my pattern (designed to fit the paper) was a bit sparse.

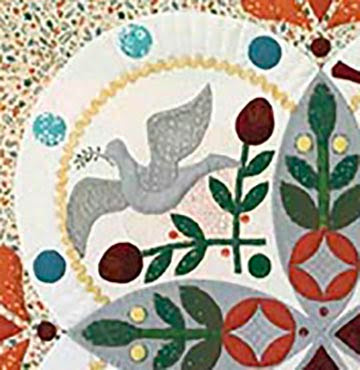

Denniele solved the space problem with a ring of fussy cut dots. Georgann says she is stealing this idea and you can too.

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llst/033/033.pdf

https://www.facebook.com/groups/325851666128986

If you'd like to buy all the patterns now for $12 in a PDF to print yourself here's a link to my Etsy shop:

https://www.etsy.com/listing/1155035028/freedoms-friends-applique-quilt-bom