Block #1

New York Tulip by Barbara Schaffer

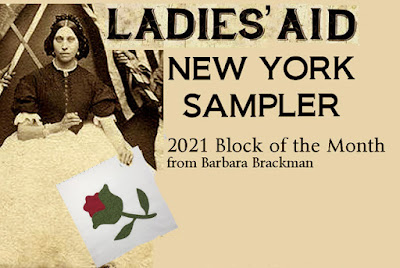

A tulip begins our 2021 appliqued BOM quilt, focused on New York's samplers and the women's work during the Civil War. Each month we look at one woman and one town's war efforts.

The woman at the center of the colorized photo is Ellen Collins

(1828-1912) working on her ledgers at the Woman's Central

Relief Association, one of the many New York Ladies' Aid organizations

we will be discussing.

The town this month is Manhattan.

New York Tulip by Becky Brown

She used repros from my Ladies's Legacy line.

When the Civil War began newspapers around the Union printed a list of items the

Sanitary Commission needed for hospitalized soldiers,

"Quilts of cheap materials, about seven feet long by fifty inches wide,"

was a request.

Women mobilized and formed Ladies' Aid organizations, often affiliated with the national Sanitary Commission (ancestor of the Red Cross.)

The Soldiers' Aid Society of Queens sent 300 articles:

Sheets, quilts, pillow-cases and cash ($200) in the first year of the war.

New York City's Woman's Central Association for Relief (WCAR) coordinated the work of smaller regional Ladies' Aid societies like the group in Queens. Ellen Collins was second in command, in charge of supplies and funds, keeping track of incoming donations and outgoing shipments to hospitals and warehouses.

Ellen's office shipped over 20,000 quilts in the first two and a half years of war.

One of the men shipping boxes of hospital supplies

from the Cooper Union building offices

is probably Samuel Bridgham (1813-1870),

Ellen's boss. The other is probably porter George Roberts.

Bridgham was once the owner of this

quilt made at the Cooper Union art school

for a hospital bed...

... signed

"School of Design

Engraving Class

Cooper

Union"

I am the fortunate owner of this Civil War souvenir, the source for the prints in my new Moda fabric collection Ladies' Legacy. Each print is named for a volunteer in the Woman's Central offices of the Cooper Union.

The quilt's backing is the document print for our

reproduction called Ellen's Comfort----

A very popular calico at the time,

small stars on a textured background.

We reproduced it in three colorways

Ellen Collins was a "reformer and philanthropist," 48-years old and single when the Civil War began. She came from a family of wealthy Quakers; her grandfather Isaac Collins established the family's successful printing business.

The Collins family lived at 41 West 11th,

in what we call the West Village,

not far from the WCAR offices.

In their 1867 account of Women's Work in the Civil War, authors Brockett, Vaughn & Bellows described Ellen's wartime role:

"The members of the Woman's Central worked incessantly. Miss Collins was always at her post. She had never left it. Her hand held the reins taut from the beginning to the end. She alone went to the office daily, remaining after office hours, which were from nine to six, and taking home to be perfected in the still hours of night those elaborate tables of supplies and their disbursement, which formed her monthly Report to the Board of the Woman's Central. These tables are a marvel of method and clearness."

The office bought or accepted donations, "assorting, cataloguing, marking, packing, storing and final distribution of nearly half a million of articles" over the years of the war.

#1 New York Tulip by Barbara Brackman

This is the center which measures about 7" x 7"

on a 15-1/2" square block. I've left room in the

corners for the secondary pattern.

Louisa Lee Schuyler was Ellen's assistant. Louisa in an obituary for her friend recalled the office systems:

"Every day old Roberts, the faithful porter...would place the [incoming] boxes in a long row and raise the lids; every day would come a corps of young lady 'Volunteer Aids' to unpack the miscellaneous articles, sort and place them in designated bins, stamp them with the stamp of the Sanitary Commission, and repack the same boxes (one kind of article only in each box now), after which they were nailed up by Roberts, appropriately marked, and wheeled off to the store house, ready to be shipped at shortest notice. A system was adopted whereby each box could be identified and traced. Miss Collins saw to it that each was acknowledged; conducted a large correspondence; made out and sent weekly lists of supplies in hand to the headquarters of the Sanitary Commission in Washington."

When the war was over Ellen's work wasn't; she continued her philanthropies with emancipated Southerners through the Freedman's Bureau and advocated tenement reform in her neighborhood by buying decaying buildings and acting as a responsible landlord.

The Block

From a New York sampler dated 1851

We've done this tulip before---in our Yankee Diary sampler a couple of years ago.

Here's Becky's.

All I can say about the floral is it seems to have been typically New York...

a mysterious importance.

One Way To Print:

Create a word file or a new empty JPG file that is 8-1/2" x 11".

Click on the image above.

Right click on it and save it to your file.

Print that file out 8-1/2" x 11". Note the inch square block for reference.

Adjust the printed page size if necessary.

Add seams.

If you are using the Hearts in the Corners set you

will want to position it like this.

Above: Pattern for the Hearts.

New York Tulip by Denniele Bohannon

You might want to buy and print a PDF of all 12 patterns now.

See this listing in my Etsy shop:

New Yorkers loved using images in the corners to link the different blocks.

Sampler with leaves in the corners from the New England Quilt Museum.

Denniele Bohannon's version from the Yankee Diary.

More about the tulip here:

Links to More Information

Read Louisa Lee Schuyler's biography of Ellen Collins:

http://civilwarquilts.blogspot.com/2019/07/my-cooper-union-quilt-samuel-w-bridgham.htmlOver the first four years of the war, someone (probably Ellen)

counted almost 32,000 blankets and bedquilts shipped out of New York.