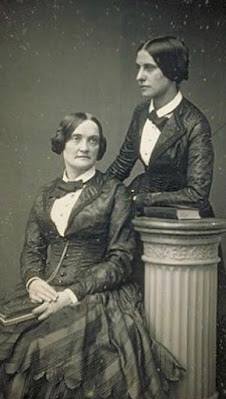

A few founding members of the Banks Brigade of Cambridge,

Massachusetts, 1863

In the fall of 1861, sixteen girls from elite families of Cambridge, home to Harvard University, met at the home of Jane Loring Gray, wife of Botany Professor Asa Gray, to begin their work for Civil War soldiers.

Jane Loring Gray (1821-1909)

The Gray's home still stands

Jane Gray's niece Julia Bragg was a member.

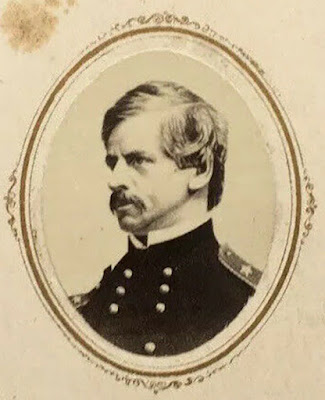

Nathaniel Prentiss Banks (1816-1894)

This local soldiers' aid society adopted the name of Massachusetts General Nathaniel Banks. The Banks Brigade (B.B.) met until 1931.

When the war was over they shortened their name to The Bee

and continued meeting to sew for charity.

Susan Hunt Dixwell Miller (1845-1924)

Sixteen-year-old Susan Dixwell became the Colonel of the Banks Brigade, due to her sewing skills and industrious nature.

In

The Story of The Bee written in the 1920s Mary Towle Palmer dedicated the memoir to Colonel Sue Dixwell. The text above is from a memorial to Sue written by William O. Dapping in 1926. He tells us she was an "expert needlewoman" having attended Miss Bowen's Sewing School (could find no further information about Miss Bowen's.) Sue was known to walk through Cambridge's central square knitting as she went.

Florence Sparks Moore (1845-1915)

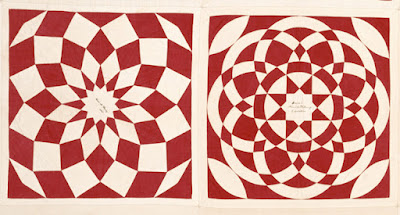

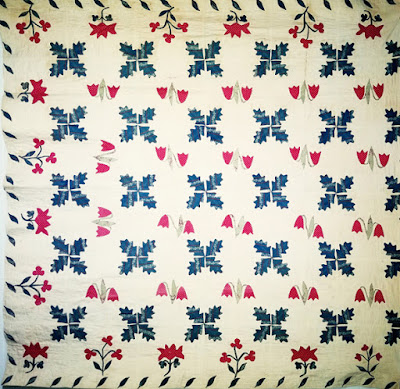

The Brigade met every Friday afternoon throughout the war to do the usual sewing of shirts, sleepwear and quilts and knitting of "blue socks with red and white borders."

Above is one of their few production accounts; the girls were not good at making lists. As the War went on they began shipping their handwork to the Western Sanitary Commission headquarters in St. Louis. No records of their quilts seems to exist.

Mary Towle Palmer (1846-? ) wrote The Story of the Bee with

help from friends like Grace Hopkinson Eliot, wife of Harvard's President.

The fifteen-year-old daughters of professors recalled they lacked

experience with plain sewing.

Elizabeth Ellery Dana (1846-1939) in the 1890s

After the war the Bee continued sewing for those in need. Lily Dana who kept a diary had been schooled at Miss Porter's in Farmington, Connecticut, an education that did not prepare her for the work of a seamstress. Grace Hopkinson criticized her awful work and Lily failed to confess.

Lily mentions carrying the Bee Basket to Mrs. Waterman's. Apparently a large basket containing work to be done was left at each house in turn and last week's hostess had to carry it to the next home (probably with manly help from a servant). There was complaining. Who filled the Bee Basket wasn't noted.

Anna Page refused to sew at all, crocheting instead.

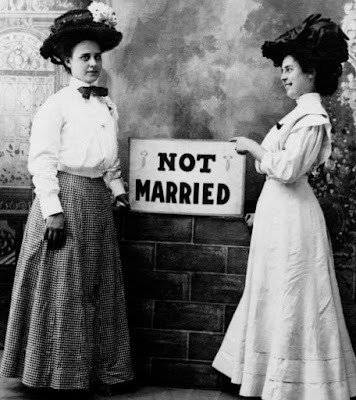

The girls grew; many married; some moved away but The Bee continued meeting every other Friday for 58 years, disbanding in 1931. Socializing, good dinners and fun was a prime motivation to join the others although some significant sewing did get done.

A 1918 parade celebrated the Bee's sewing for four wars.

Lilian Horsford Farlow (1848-1927)

Lilian rented a truck for the parade and furnished it with

rocking chairs for ten Bee members who knitted and saluted soldiers.

The original 16 invited others to join after the Civil War. In all, over 60 women belonged at some time or another, among them the two Alice Jameses of Cambridge.

Miss Alice James (1848-1892) joined when the family moved to

Cambridge in 1867. Her brothers were William, the

philosopher, and Henry, the novelist.

Mrs. Alice Howe Gibbens James (1849-1922)

married the Harvard philosophy professor.

Bee members found her sister-in-law entertaining

& witty. Did Mrs. Alice?

Well, one could go on. The Banks Brigade and the later Bee are one of

the best documented of the local soldier's aid societies.

Do read Mary Towle Palmer's The Story of the Bee at Cambridge's history site:

And Cambridge has a Flickr page full of the members' photos, which is where many of the above portraits were obtained.

Litchfield Historical Society

Scrap of a dress Jane Loring Gray recalled wearing in 1847, stripes in Prussian blue.