.jpg) |

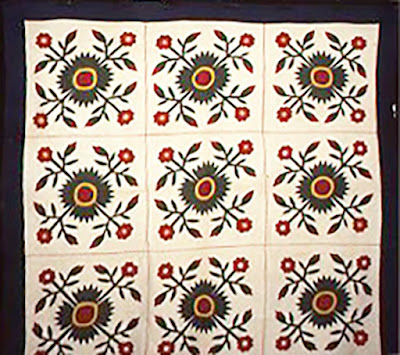

Sampler applique quilt that descended in the Wyse family

of Columbia, South Carolina with a family tale related

to the Civil War, a gift for soldier Allen M. Wyse.

He and Marilla Elizabeth Riser, one of the women who signed a block, married after the War and lived near the town of Prosperity in Newberry County until they moved to Columbia in later life.

Prosperity is in an area known as the Dutch Fork, due to the Deutsch (German) settlers. By their names the Risers and Wyses would seem to be German. Allen's unusual middle name Melanchton honors Philip Melanchthon, a German Lutheran associate of Martin Luther.

Town of Prosperity in the 1880s

Mary's tale:

"This quilt was made for my grandfather, Allen M. Wyse (1846-1929), to take with him when he entered college....He [joined] the Confederate army (Company A, Twenty-Fifth Regiment, Infantry in 1863. The squares were appliqued by girls of the community [from] material which had been bought in a piece by his mother. They were then put together at a quilting party in the family home near Wyse's Ferry on the Saluda River not far from Prosperity....One of the squares was made by the girl who later became Allen's wife, Marilla Riser."

Family Search records indicate they married in 1866 but do note that Gertrude and the other children arrived in 1873 and later. The 1870 census shows Marilla Riser at 23 (without occupation) living with her parents and siblings. She was not yet married.

South Carolina's Saluda River is the boundary of the Dutch Fork

We see evidence of a later date in Dutch Fork culture and the album quilt itself. The German immigrants who'd lived in Newberry County for a few generations made their beds in different fashion from neighbors of British descent until about 1880 when they adopted the "English" style of sheets and blankets rather than feather comforters. When analyzing patchwork quilts in the area for the South Carolina quilt project Laurel Horton found, "Nearly all the quilts surveyed dated from the late 19th or early 20th century." German-Americans there would not have been stitching appliqued album quilts in the early 1860s when Allen went off to college.

The red is not this pinkish, but probably a brighter, deeper Turkey red solid.

The greenish-blue, the familiar late-19th-century teal color from new synthetic dyes.

The fabrics are all solid colors, the kind of cotton produced by Southern mills after the Civil War. Mary Boozer had a different opinion about the choice of solid, primary colors: The fabric: "Clearly made for utility in strong, masculine colors." Born in the early-20th century, Mary was too young to recall the limited choices in Southern stores and attributed the typical fabric choices to taste not trade.

The blocks are set in a triple-strip sashing, a hallmark of late-19th-

century Southern design. While the floral wreath might have been

made anywhere in the U.S. after 1840 or so there are three wheel

designs found primarily in the Carolinas late in the century.

Repeating arms in a circular pattern with

reverse applique

From the Lexington Museum in the Dutch Fork,

a better picture of this quilt locally called Sundew.

Similar fabrics

An empty flange between the blocks. If it had

a cord inside we'd call it piping.

Read a post about the quilts of the Dutch Fork here: http://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2020/04/quilts-in-dutch-fork.html

.

.