Cassandra's Circle #11, Charleston Star by Becky Brown

Susan Dupont Petigru King Bowen (1824-1875)

Sue was one of Charleston's literary lions, a Charleston star before the war.

Sue Petigru King was at the periphery of Mary Chesnut's circle much of their lives. Charleston girls of good family, they attended Madame Talvande's elite school together there when they were young. Mary thrived; Sue despised it.

James Louis Petigru's Charleston law office, photographed

in the 1930s. Library of Congress

In the early 1840s both young women married lawyers who'd done their clerking in the office of Sue's father James Louis Petigru, one of Charleston's most brilliant attorneys. James Chesnut moved his bride back to his home town of Camden. Sue stayed in Charleston with Henry King, who never fulfilled any promise he might have had. Sue was not enamored of Henry, whom she

described as short, broad, round-shouldered and ''a little lame.''

Sue and Henry spent the first years of their marriage living

with his family at Meeting and George Streets.

Henry was an alcoholic who could not support her in the manner her ambitious mother had hoped for. Within a few years she and her unhappily wed sister Caroline were making regular husbandless escapes to New York City and Sue was writing novels about miserable marriages in Charleston. She began publishing anonymously in 1853 to much success.

Charleston Star by Susannah Pangelinan

The Mills House

In the spring of 1861 as war threatened, Mary Chesnut was in Charleston boarding at the Mills House. She heard local gossip from Sue, now formally separated from her husband.

James Louis Petigru (1789-1863),

reputed to have countered Secessionist talk with:

"South Carolina is too small for a republic and too large

for an insane asylum."

Charleston Star by Denniele Bohannon

That same month Abraham Lincoln sent friends Stephen Hurlburt and Ward Lamon to Charleston to interview Sue's father. James L. Petigru had long been opposed to the standard South Carolina dogma on state's rights. From nullification through Governor Pickens's threatening the Union's Fort Sumter James Petigru was a dissenting voice.

Stephen Hurlburt, born in Charleston, wrote a report to the new President about the city's mood:

"There is an unanimity of sentiment which to my mind is astonishing...no attachment to the Union.... Fort Sumpter is the only spot where the United States have jurisdiction and James L. Petigru the only citizen loyal to the nation."

Women watched from "Housetops in Charleston During the Bombardment of Sumter"

Harper's May, 1861

Fort Sumter was soon under Confederate jurisdiction but Petigru maintained his Union loyalty. Daughter Caroline shared his sentiments and fled to New York and Europe while James Petigru stayed in Charleston, where he enjoyed respect from the many who disagreed with him so dramatically. Sue---if she cared at all---was a Secessionist. When Henry King died after the Battle of Secessionville in 1862 Mary wrote: "He died as a brave man would like to die. From all accounts, they say he had not found this world a bed of roses.”

Charleston Star by Pat Styring

The widowed Sue darts in and out of Mary's diary, primarily viewed as a fast woman who was enthralled with the soldiers, throwing off her widows weeds for scarlet. In their book about the Petigrus Jane & William Pease quote a former Charleston gentleman after the war: "There goes Mrs K[ing] driven by a Yankee thief in my uncle’s Stolen Buggy.”

Photo of Susan King Bowen from

her sister Caroline's album. The frizzed

fringe on her forehead indicate an 1870 date or later

when she was about 50.

But George Williams was an admirer of Sue in Charleston in 1863, writing his niece:

"I have a very dear friend at Summerville, Mrs Henry King, the author of 'Busy Moments of an Idle Woman, Lily etc.' I go up there occasionally...Mrs. King is as kind to me as an own dear Sister. Since this war began, she has lost her husband, Father, Father in law, beside several other friends. She is one of the most brilliant women in America."

She must have been a charmer, but Sue was volatile, stubborn and self-absorbed, so difficult to live with that her relatives used words like "nearly mad" when complaining about her. Her father described her as a woman who thought she was infallible: "Whoever differs from her---must be wrong---mental hallucination."

The Petigru's family story is fascinating and I've told parts before. After the war Sue continued to scandalize by marrying Christopher C. Bowen, a sleazy Congressman who apparently had two legal wives already. Sue died of typhoid ten years after the war.

Grave of

Susan Petigru Beloved Wife of Christopher C. Bowen.

Bowen and her father may be the only persons Sue ever cared for.

The Block

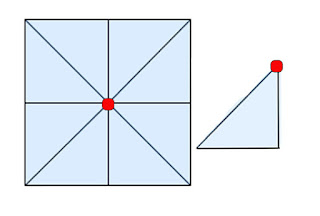

The inspiration is a block in an album quilt from Stella Rubin's shop.

Applique to an 18-1/2" square or cut it larger and trim later.

One way to print these JPGS.

- Create a new empty JPG file that is 8-1/2" x

11" or a word file.

- Click on the image above.

- Right click on it and save it to your file.

- Print that file out 8-1/2" x 11". Note the inch

square block for reference.

- Adjust the printed page size if necessary. Do not use

tools like "Fit to page."

- Make templates.

- Add seams when cutting fabric.

For the wreath cut a 15" square of fabric. Fold into triangles.

Place the template on the pattern with the center at top. Add seams and cut 1.

You need one 4" rose for the center.

Becky's Rose

Julia Jones's block from Gay Bomers 1857 Album

at Sentimental Stitches

Four blocks from an album by Elizabeth Dilts, Hunterdon County, New Jersey

New Jersey Project & the Quilt Index

Cassandra's Circle: Blocks 1-11

Susannah Pangelinan

Quilted, bordered and bound.

Two final blocks to go.

Extra Reading

Read Jane H. Pease & William Henry Pease's

A Family of Women: The Carolina Petigrus in Peace and War. Preview:

https://books.google.com/books?id=dtnwGSZuztsC&dq=sue+petigru+king&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Read two of the novels that made Sue a literary Charleston Star: