Eight blocks by one hand, one by another?

"Made by Gradma (sic) Miller In 1858 - Given To Grand (sic) Steele In 1902

From Her Mother Temperance Van Winkle"

Inked inscription.

See more about dating the quilt last week:

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7217936/temperence-van_winkle

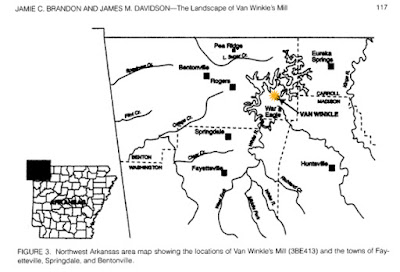

Map. Benton County's Van Winkle Hollow in relation to today's geography.

Jamie C. Brandon & James M. Davidson have

published much archaeological work on the family.

By the time of the Civil War in 1861 Tempy was living in a large house with her eight children, their tutor and at least one mill worker near War Eagle, Arkansas on the White River. The 1860 census lists the Van Winkles with 12 slaves, included in his property worth almost $43,000. Their wealth came from the slaves, thousands of acres of Arkansas land and two mills that Peter Van Winkle built.

Daughter Mary, another Molly, married the mill's former lathe carpenter

John Belle Steele of the First Arkansas Calvary

after the war in 1866.

Arkansas was tortured by guerrilla warfare and shifting loyalties during the Civil War. The Van Winkles were Confederate sympathizers, milling lumber for the Confederate Camp Benjamin and naming their war-born children after Southern heroes.

Peter & Tempy in the 1860s

Two of the boys born during the war:

Jefferson Davis Van Winkle and Robert E. Lee Van Winkle.

Tempy gave birth to 12 children; 9 lived to adulthood.

In 1862 frightened by harassment and worried about losing their slave property when Union troops took over (they lived about 15 miles from the Union state of Missouri) they moved the slaves and what they could carry to Texas where Tempy had many relatives. Two of her children died in Texas. While they were gone eldest son Calvin died in the Arkansas fighting.

While they were refugeeing in Bowie County, Texas Confederate sympathizers burned the saw mill to prevent the Union from using it. Their house went too. The story often retold is that Peter Van Winkle buried $4,000 in gold in Van Winkle Hollow but like most caches of Civil War gold it has never been found and probably didn't ever actually get buried.

Southern refugees by Thomas Nast ,1863

Refugee's stories were often sentimentalized to the point that the actual unhappy stories are forgotten. Tempy's is one of them. She lost three children during the war and nearly everything she owned.

And what of the enslaved people forced to walk to Texas? Who stayed and built new lives after the war. Who went home to Arkansas?

Post-war lumber mill

When the white Van Winkles returned to their burned out businesses and home they rebuilt. Peter's new mill was modern, efficient and successful, becoming the largest lumber mill in the region, supplying building material into Missouri and Kansas until it closed in 1890 eight years after his death. Daughter Ellen's husband James Blackburn bought it but he apparently didn't have Peter's financial skills. An obituary notes: "This

investment almost proved to be his financial Waterloo in later years but he finally

pulled through and left his estate in order. He lived at the mills until 1890...." Ellen died in 1884.

The post-war House with 11 rooms was destroyed in 1969.

The site, Van Winkle Hollow (also called Van Hollow), is now Hobbs State Park

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History

This photo of the family in the newly built house in the 1870s

shows the landscape. The Van Winkles fit a plantation-style house

into a narrow Ozark "hollow," a rocky river valley

Men who'd been slaves in the mill before the war returned to work for wages and worker housing was constructed in the hollow. Local historians have identified at least two: Lathe turner Aaron Anderson

Van Winkle and his wife Jane and teamster Perry Van Winkle and wife Agnes. Each family had nine children who grew up in Van Winkle Hollow.

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History

Temperance in the white cap with her family

on Mary's front porch in Rogers, Arkansas in 1901,

the year before she died at 77 years old.

Aaron Van Winkle is the black man standing behind her.

Mary may be the woman on the top left.

Mary and her husband built a house modeled on her parents' country home

at 303 South 1st Street in Rogers, Arkansas; recently demolished.

See Aaron Van Winkle's grave and obituary here:

Van Winkle family quilt in the Rogers County Museum collection

We can guess this quilt was stitched by Temperance Miller Van Winkle (1825-1902) given to her daughter Mary Van Winkle Steele of Rogers, Arkansas.

Mary Van Winkle Steele (1841-1922)

from her Find-A-Grave site

One of Mary's grandchildren inked the inscription years later, recording what was remembered of its origins.

The mill on the White River's been recently rebuilt as the

War Eagle Mill, a grist mill.

Van Winkle men have been extensively examined by historians and archaeologists looking at the material culture of the place. Here we try to link the quilt, women's work.

References

"The Landscape of Van Winkle's Mill: Identity, Myth, and Modernity in the Ozark Upland South,"

Jamie C. Brandon and James M. Davidson. Historical Archaeology. Vol. 39, No. 3,