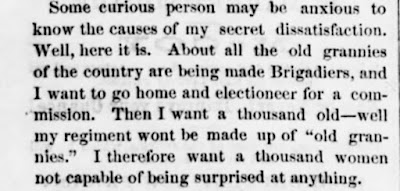

A Maine Quilt made for soldiers with each block quilted and bound and then stitched together. What we call "potholder style" construction.

Frank Leslie's Illustrated

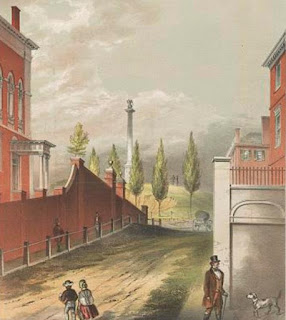

Building housing the Clayton General Hospital in Harper's Ferry, Virginia

Abba Ann Goddard (1819-1873) was a multi-talented woman who served as matron at a Union hospital in Harper's Ferry, Virginia while writing lively dispatches for Maine's Portland Daily Press.

Her father was a mechanic at the Lowell, Massachusetts textile mills and Abba worked in the mills herself. She began her writing career in 1841 as the 21-year-old co-editor (with Lydia Hall) of the female mill workers' periodical The Lowell Offering.

Mill employees in front of their boarding house, probably 1870s,

long after Abba's time there. I could find no pictures of her.

She moved to Troy, New York in the mid 1840s to teach at Emma Willard's Troy Female Seminary and then to Maine. When the war began she followed the Tenth Maine Infantry south as nurse and reporter with four other Portland women.

September 9th, 1862 letter

She advised the army on strategy and promotions in her "Letters from Harpers Ferry"

and thanked the people of Maine for their donations of food, clothing

and bedding.

Women in Saco, Maine, mentioned in Dr. Dawson's letter, stitched this donation quilt.

National Gallery of Art

Siege of Maryland Heights by William McLeod

The town and her hospital passed into Confederate hands for a few weeks in September, 1862 as Stonewall Jackson's troops took over.

Library of Congress

Photo by John P. Soule

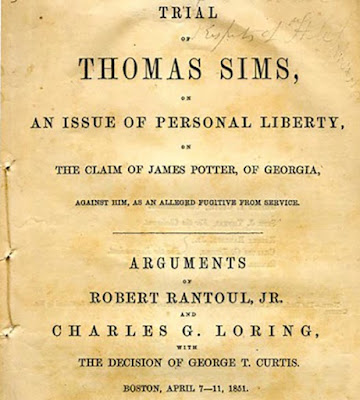

Union controlled Harper's Ferry had become a haven for escaped slaves, known as contrabands for their position as confiscated Confederate property.

Jackson's troops under Major General A.P. Hill horrified the locals by kidnapping the Black residents, sending many back to their slavemasters and selling others into new servitude.

In her accounts Abba wrote:

“Every nook, cranny, barn, and stye has been searched and men, women, and little children in droves have been carried off…our hospital laundresses, and our men servants, without a word of warning, were seized upon...”

Abba manage to shelter a few employees in the building's cellar until the Union Army recaptured the town, writing in her account of that September:

“I am almost tired of night watching and my revolver begins to grow weary."