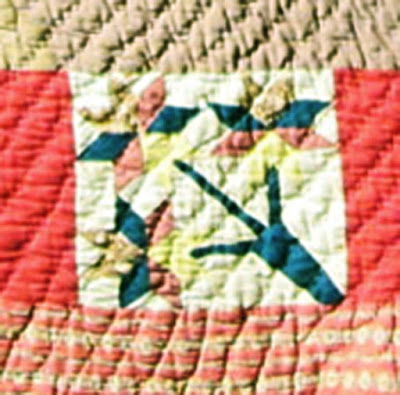

A well-worn quilt seen online. In setting and quilting style, fabrics and color it seems a typical late-19th-century Southern quilt, quite charming in its naive interpretation of a popular pattern, stitched in the inexpensive, gauzy, likely-to-fade-cottons from post-Civil-War Southern mills. Is that a linsey stripe along the bottom or just an all-cotton red and white ticking kind of fabric?

Typical colors often seen in Southern quilts from the era include the plain chrome orange and a brown. That brown might have been red once, but plain brown is also typical of late-century Southern quilts.

Here's the block, a variation of a popular pattern often called Peony or Cleveland Tulip after President Grover Cleveland who was president twice from 1885–1889 and 1893–1897, which is probably when this quilt was made: 1885-1900.

Several pattern companies sold the design. Is obvious that the quilt above

was not a "book pattern" although it may have been inspired by a commercial design.

Variations on the design go back to the 1840s

Similar pattern documented in the Tennessee project,

from the Weaver family of Knox County.

Collection of the East Tennessee Museum.

Solid colors, same block, but placed on point.

The quilt at the top of the page was on display at a museum in Gaffney, South Carolina (a town about 20 miles from Charlotte, North Carolina). The photos were taken about 6 years ago.

Here is the label, indicating it was made in the mid-19th century by a Blackfoot woman named Bluesparrow (1797-1905) who lived in North Carolina and later in Kansas. The label indicates the blues were hand dyed with indigo (possible) and some of the reds "possibly with beet juice." Not plausible. Beet juice will not color cotton red in any washable fashion. The quilt is probably not hand-dyed but stitched from local fabrics dyed in local mills.

Bright red cottons that remain so bright were probably

commercially dyed with a synthetic Turkey red as in this similar

quilt from the late 19th century. The yellow orange was the

mineral dye chrome orange. The green???

What is even more implausible---and unfortunate---is the story that the quilt is an "escape code" quilt:

"Legend has it that Bluesparrow would take slave children, put them in her laundry basket, and cover them with this quilt. She would then walk out to the perimeter of the woods, where their parents would retrieve them and escape. It has also been said that Bluesparrow would hang these quilts on the drying line with the patchwork posies growing in one direction, while one patch would point out the direction of their trail or escape route."The pattern name they say is "Freedom Flowers."

"Legend" may have it---but there is absolutely no truth to such a story. The quilt was made about 25 years after slavery was abolished. And even if this quilt were as old as 1850 the underground railroad link is untrue. No one has ever come up with any plausible evidence that any quilt "pointed in the direction" of an escape route. It makes no sense.

Collection of Kathy Sullivan

The heavy sashing bars (a late-19th-century Southern style characteristic)

have faded to a pale tan here.

It's a poetic tale, but untrue. Now, why do I care about quaint legends on museum quilt labels perpetuating myths? Because we know nothing of the true story of Bluesparrow, of this quilt and far too little about quilts made in the Cherokee nation either during the Civil War or after. Re-telling and re-hashing stories like the underground railroad quilt code legend absolves museum personnel of researching any kind of actual, accurate local history.

Tell them Betsy Ross sewed a flag and we've done our bit for women's history; tell them escaped slaves used quilts as maps and we've covered Black History month (why does it only get a month?)

Don't get me started.

Here's a Southern beauty from Pepper Cory's collection.

Freedom Flowers, my foot.

7 comments:

In other words the label has no truth to it.

I cannot conceive why a museum would not actually investigate history and be honest about the quilt history, or if they don't know just don't write fiction.

I homeschooled and when my kids were younger we did use beets to dye a cloth to make an "Egyptian" robe- definitely more purple then red!!

It’s actually unfortunate that fallacies are passed as truth for the next generation to believe.

I've heard the underground railroad myth mentioned in conversation as fact several times, and I have you and your research to thank for my ability to (gently) refute it every time!

I wonder how many of these underground railroad myths (and the buried with the silverware quilts) are stories that started with a tiny bit of truth. Perhaps the family was involved in underground railroad. Perhaps there is a quilt in the family for generations that no one knows when it was made or even how it was acquired (made by family? won in a sanitary aid raffle? swiped by a civil war soldier?) and someone combined all these bits into a story that became family lore. The story may have been accidental due to speculation and lack of research. Or on purpose to make the family or quilt seem more important somehow. I'd bet far fewer quilts, no matter how tatty, with the underground quilt lore attached got thrown on the burn pile than those that didn't have the story.

I can give the owners of the items a pass, as they probably have no idea how to start researching the facts. Or maybe they don't want to know if the family story is true or not. But a museum should not be in the business of continuing such myths. Is now when I throw in a "Harumpf!" ??? :-) On the other hand, small town museums may not have the resources for research either.

When you get items like this, do you let the museum know of the errors? And if so, do you ever hear back from them?

Amen, Barbara! I get asked about the "Underground Railroad Code" quilts all the time. I answer with quotes from your book, "Facts and Fabrications..." I'm so glad you wrote it. Too many history teachers across America had been teaching the false code in their curriculum. No more false history, PLEASE!

A few years ago we had a speaker come to our small local Historical Society and talk about Underground Railroad Quilts. She mostly had the story and quilt book as her research. When she did mention that the truth of the source family's story had been questioned, the African Americans in the room became angry and upset. One woman, a teacher who had included the Underground Railroad quilts as part of her classroom teaching, asserted that questioning the Underground Railroad Quilt stories was just another attempt by white people to suppress black history. Discussion became quite heated. It was a disaster.

Post a Comment