This album quilt in the collection of the Clara Barton

Birthplace Museum is one of the most famous

quilts associated with the Civil War.

It was probably made to memorialize a veteran's re-union, called an encampment, in the 1870s or '80s. Forty-eight men's names are inked in the blocks. The central square is inscribed:

"Post 65 of the G.A.R.

Clara Barton Encampment

Warren Mass

Organized August 1868"

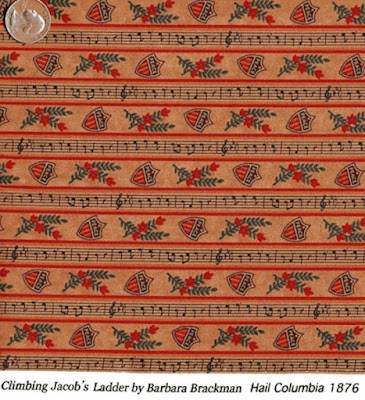

The quilt is not dated (the post's organization date of 1868 is on there) but the fabric in that dedication block is a stripe printed to celebrate the 1876 Centennial.

The shield is inscribed Peace and the musical notes are thought

to be from the song "Hail, Columbia." This piece is a reproduction

that the Museum did with Windham Fabrics several years ago.

I had a swatch and also reproduced the stripe ten years ago or so.

Based on the fabric the quilt is dated to the late 1870s, about the time of the Centennial celebration that created a revived fashion for patchwork quilts. G.A.R. veterans' groups were named for Civil War soldiers and it's a tribute to the men of post 65 that they named theirs after a woman. One might think the quilt was made or given to Clara Barton herself, but it is more likely it was donated to the Museum because of her name in the inscription.

The quilt is famous because Clara Barton is famous. But why is Clara Barton so famous? She was only one of hundreds of women who worked in Civil War hospitals, yet of those hundreds the one chosen to be pictured in the frontispiece of the 1867 book Woman's Work in Civil War, the standard for remembering female contributions to the Union cause

She's inspired dozens of biographies while most

women hospital workers have been forgotten.

Of course she is remembered as the founder of the American Red Cross, and that organization has had a dynamic public relations and fundraising presence in America since then, but the Red Cross was founded in 1881, years after the War.

.

Her service during the Civil War doesn't seem extraordinary.

Clara Barton (1821-1912)

probably about 1850.

Clarissa Harlowe Barton was born in Massachusetts. As a single woman she worked to support

herself, first as a school teacher and then as a clerk in the U.S. Patent Office in Washington, beginning in 1854.

The Patent Office during the Civil War.

The building wasn't finished until 1868.

Barton is sometimes referred to as the first female clerk there---but as with most "firsts" this is doubtful. Women had been hired to copy documents working from home. What was unusual about her hiring is that she is supposed to have been paid the same salary as the men in her position and she had more duties than mere copying. She went back to Massachusetts after a few years, either because she was let go in the new Buchanan administration or because her family needed her nursing skills at home. While depressed and feeling aimless at home "she pieced together a quilt," according to a letter. In 1860 she was back in Washington as a copyist.

She attended Lincoln's inauguration.

A year or so later wounded Civil War soldiers began appearing in Washington's make-shift hospitals (the Patent Office set up wards) and Barton began visiting, providing consolation, companionship and what medical assistance she could.

She became skillful at organizing relief supplies and incoming food and provisions, a role that quickly became a standard for concerned women. As the war dragged on she apparently quit her clerical job and followed the fighting. In 1863 she moved to the Union-occupied Sea Islands outside Charleston, South Carolina and delivered and supervised supplies, working with soldiers and freed slaves. She ended the war in Virginia at a hospital under General Benjamin Butler.

Two unnamed women working in Virginia in army food service

Barton may have been a skillful organizer, a compassionate bedside visitor and a woman who stood up for her own rights and those of her patients, but she was one of hundreds. Why is her name the best remembered?

The Sanitary Commission and the Christian Commission were

two large Union organizations that delivered goods and provisions

to soldiers in the field.

She certainly was a celebrity. In doing a search for Clara Barton in the Library of Congress's digital newspaper page I got 14,947 hits. The earliest published reference I could find was in July, 1864 when she is listed as one of the organizers of a home for disabled soldiers in New York. Up to that time Clara Barton was not famous.

As the war ended she was back in Washington and made a move that may have insured her celebrity. She realized that there were thousands of unknown soldiers' graves, thousands of missing soldiers and thousands of bereaved families hoping to find something about their lost men. She'd been keeping records in her hospital work and she organized a system to cross reference information.

Sign from the Missing Soldiers Office Museum in Washington

President Lincoln appointed her General Correspondent for the Friends of Paroled Prisoners in March, 1865. She established the Bureau of Records of Missing Men of the Armies of the United States where she and 12 clerks answered tens of thousands of letters about the missing. They compiled long lists of soldiers who were unaccounted for and checked prison camp, burial and hospital records. The Missing Soldiers Office Museum tells us that her office identified more than 22,000 men by 1868.

In the last weeks of the war she sent a press release to newspapers all over the country.

A Mineral Point, Wisconsin paper printed this notice:

"Paroled & Exchanged Prisoners

In view of the great anxiety felt through the country for the welfare of our prisoners now being exchanged...Miss Clara Barton...had kindly undertaken to furnish information by correspondence in regard to the condition of returned soldiers [...and] to learn the facts in reference to those that have died in prison, or elsewhere. All letters addressed to Miss Clara Barton, Annapolis, Maryland will meet prompt attention. Editors throughout the country are requested to copy this notice."

A few months later:

"Miss Clara Barton has hit upon an excellent device for bringing to the knowledge of friends the fate or whereabouts of missing soldiers....She has already received such descriptions in some thousands. Roll No 1 is a large sheet [with] fifteen hundred names of missing prisoners of war. Twenty thousand copies of this roll have been printed and circulated....The rolls of soldiers were posted in post offices, on newspaper office windows and in newspaper columns. Her name was in some paper somewhere nearly every day in the summer of 1865 when she traveled to the Andersonville prison to collect names and provide headboards for the graveyards there. In March, 1866 Congress voted unanimously to pay her $15,000 in bonds to continue her work (an enormous sum of money.)

In 1867 we find references to her lectures on the prison at Andersonville, the rolls of missing soldiers and her war work.

Davenport, Iowa, 1867

Barton was good at organizing, at inspiring others, at public speaking and apparently she was excellent at public relations. She encouraged families across the country to describe their missing, asked veterans to help with identification of fallen comrades and publicized the "Rolls of Missing Men". As we can see from the newspapers it was Clara Barton in charge. One did not write to a department or an agency. "All letters must be directed to Miss Clara Barton, Washington, D.C."

Celebrities were featured on cartes-de-visites,

collectible photographs

It is probably this post-War work that landed her at the front of the book Woman's Work in Civil War.

But it's not that work that is remembered in the many subsequent biographies. A woman good at managing a federal bureaucracy was not a salable 19th-century image. She was remembered as a caretaker, a nurse, "the Angel of the Battlefield," an acceptable female role.

Clara Barton, Girl Bureaucrat was not a viable book title (although I might have liked it as much as I liked all those nurse biographies from the 1950s).

"My work has been chiefly to supply 'things.' "

If you are interested in the real Clara Barton see the 1987 biography Clara Barton, Professional Angel By Elizabeth Brown Pryor.

Google Books Preview here:

https://books.google.com/books?id=gmaFUNcR4zkC&printsec=frontcover&dq=pryor+brown+clara+barton&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjW0sKtta3gAhUm4IMKHVU6A4MQ6AEIKjAA#v=onepage&q=pryor%20brown%20clara%20barton&f=false

Windham fabrics did a Clara Barton collection

based on the album quilt. Here is some of the

yardage---fake patchwork.

12 comments:

Thanks for the mini biography. I find Clara Barton's actual history far more interesting than her idealized "Angel of the Battlefield" role!

Me too. She must have been a dynamo.

Almost finished Aunt Becky (ironically while waiting in hospital with my husband's deeply gashed finger LOL) - it is an exceptional book. So Clara looks like another to add to my list - what great girls that put humanity first.

Thank you :D

Fascinating! So many strong women behind the scene working hard!

Love the alternate book cover! I learned about so many Famous Americans from reading that series. I also read (many times) "We Were There With Clara Barton," from another juvie series. That one had a chapter on her Red Cross work at the Johnstown Flood. According to that author Barton rescued a child from a rooftop (floating in the water), singing "Jesus, lover of my soul, let me to thy bosom fly / While the nearer waters roll / While the tempest still is nigh." Obviously that scene made an impression on me. :)

Clara would have been 70 during the Johnstown Flood. What a woman.

Clara was a woman ahead of her time! I have some of that cheater fabric--reading this story makes me appreciate it more

Fascinating. Thanks for the information on Clara Barton. I never wondered WHY she was famous.

Alice- my experience has been that famous people often have a good publicist---Clara's was herself.

Great story, thanks.

Barbara, can you tell me if any of the "Rolls of Missing Men" still survive? I have researched a dozen or more Civil War Union soldiers, and a couple of them were listed as missing. I would love to know where any printed, transcribed, or digital copies are located, because I would like to see if those men are listed. Thank you for the information about Clara Barton.

The photo of Sally Tompkins coat at the Tompkins Cottage Museum was not taken by Lori Jackson Black. Lori took the photo of the quilt, and I took the photo of the coat. For more information about the Tompkins Cottage Museum and Sally see https://www.mathewscountyhistoricalsociety.org/sally-louisa-tompkins.html

Becky Foster Barnhardt

Curator, Tompkins Cottage Museum

Post a Comment