Mary Ann Poindexter's mother & sisters made this quilt dated 1852 for her marriage to John Marshall Staples on September 30, 1852.

Her mother Elizabeth Daniel Poindexter was born in Todd County, Kentucky about 1807 and married Peter Poindexter on September 12, 1825.

In the early 1830s the Poindexters moved to Illinois with three young children and stayed about ten years. Elizabeth gave birth to two children in Illinois and after about a decade they moved west to Missouri, settling near the town of Lone Elm in Cooper County, 10 miles south of Boonville where Peter was recorded in the 1840 census.

A few years later her husband disappears from the records. The 1850 census finds Elizabeth living as head of her household with eight children, the youngest Sally was five. Had he died in the late 1840s?

Preparations for daughter Mary Ann's 1852 wedding to John Marshall Staples are said to have included stitching this quilt.

Elizabeth's daughters Verlinda and Martha, 22 and 18, may have contributed as did girls Susan, Elizabeth and Sally all under ten. Martha had married about six months earlier than her older sister. Did Martha Poindexter Cullars get an elegant quilt too?

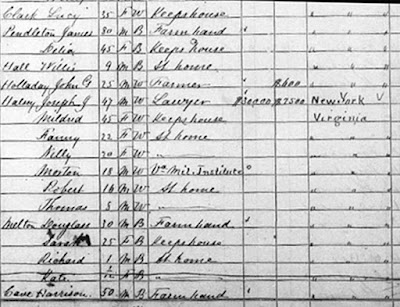

Missouri was a slave state. Although the economy did not encourage large-scale plantation farming, many Cooper County immigrants brought slaves with them. We might guess the Poindexters and the Staples maintained slaves in their households and a check of the 1850 Cooper County slave schedule lists 14 with the Staples family before John married Mary Ann.

Mother Elizabeth did not live to see the Civil War in Missouri; she died in 1858 at 51. That year her youngest Sally (only 13?) also is recorded as marrying.

A young man named Anderson Staples who said he had been a slave in John Staples's home joined the Union Army's Colored Troops Company H from Boonville in 1863. He was born in Missouri about 1842 to parents Jane and Samuel Poindexter who received a pension for his service.

Jane and Samuel's marriage was recorded in 1868 by the Missouri Freedman's Bureau. (They were not actually married in 1868; in October they and many other Missouri slave couples recorded their standing unions.)

The African-American Poindexters may have come from Kentucky with Elizabeth and Peter. Jane may very well have had a hand in this quilt.

Anderson's story ends with his enlistment. Perhaps he died young in the war as his pension went to his parents and not a wife.

The earliest record I've found in the files of Family Search is from 1873, a check going to Private Anderson Staples's parents who lived in Boonville.

Mary Ann's husband John Staples died in May, 1865 a few weeks after the truce at Appomattox Courthouse. She was left with five children under twelve; the youngest girl Johnnie Marshall Staples born that year named for her father after his death.

The widowed Mary Ann gave the quilt as a wedding present to her younger sister Elizabeth who married William Park Gunn on August 18, 1872. The Gunns moved to Sherman, Texas taking the quilt with them.

See the quilt here at the Quilt Index in the D.A.R. Museum files.

https://quiltindex.org//view/?type=fullrec&kid=16-12-286