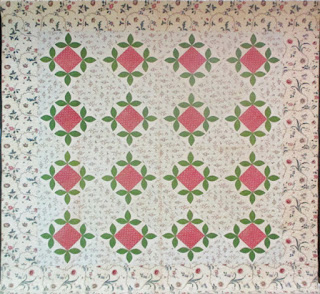

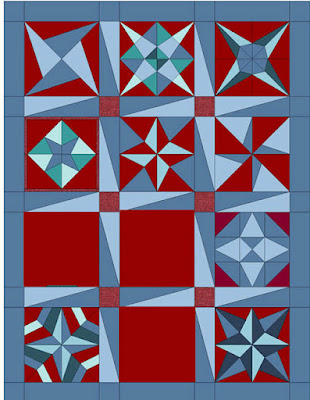

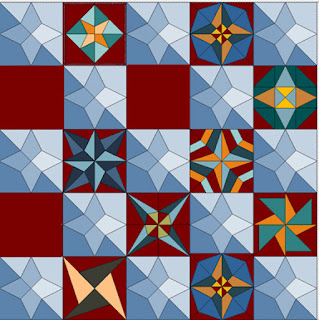

Block #7 Honeybee for Abigail Goodwin by Becky Brown

Abigail Goodwin (1793-1867)

From William Still's Underground Railroad

"From my long residence under the same roof, I learned to know well her uncommon self-sacrifice....No friend of hers would for a moment think of permitting that miserable caricature, the only picture exisiting....to be given to the public...so mournful and ridiculous a misrepresentation of her interesting face."

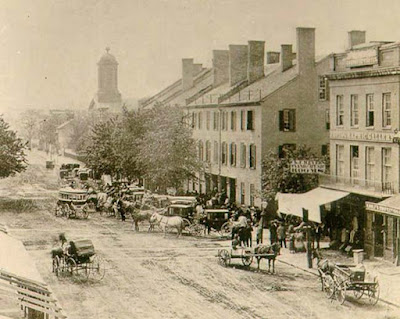

Abigail was a life-long resident of Salem, New Jersey, a town

founded by Quakers with a port linked to the Delaware River

and regular steamship service to Philadelphia.

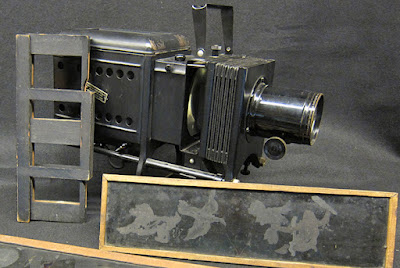

The Delaware, its tributaries and canals were a nautical branch of the underground railroad.

Salem is southeast of Philadelphia about 40 miles.

The wharf in Salem

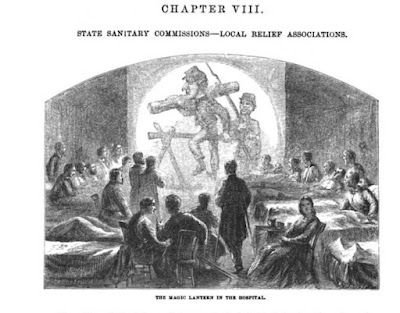

William Still remembered Abigail Goodwin: "New Jersey contained a few well-tried friends, both within and without the Society of Friends [Quakers]" She was "one of the rare, true friends to the Underground Rail Road."

Quakers and free Blacks aligned in breaking

the law in the 1850s.

In his book Still assigned roles to the people and places using railroad metaphors---agents, stations, station masters, conductors and stockholders. Abigail was a station master who spent much of her time persuading "friends to take stock in the Underground Rail Road," in other words, to donate to the movement. Fundraising, collecting coins for the cause, was a major occupation. Abigail spent little on herself. Her wardrobe, as several noted, was in worse shape than that of the refugees she clothed.

Honey Bee by Denniele Bohannon

continued to live with Abigail as shown in the 1860 census although by this time Jonathan and Sarah Woodnutt (Abigail's elder sister) were listed as the household heads as Betsy died that year.

J. Miller McKim (1810-1874)

As William Still wrote:

"His fate was not different from that of his colleagues, in respect of interruptions of his meetings by mob violence, personal assaults with stale eggs and other more dangerous missiles."

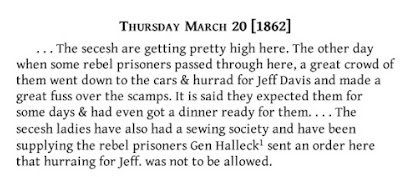

Rioters stoned the Goodwin house.

The Goodwin sisters were two of six daughters of William and Elizabeth Woodnutt Goodwin of Salem: Betsy and Abigail remained single, sisters Prudence married and Mary and Sarah married the same man---a Woodnut cousin--- in succession. Another sister is unaccounted for.

The Block

Block #7 is one of the early applique designs drawn from a quilt dated 1844

by Sarah A Smith of Swarthmore, Pennsylvania.

Much like a quilt in Debra Grana's collection

found in Vermont.

Debra showed hers at an AQSG exhibit a few years ago.

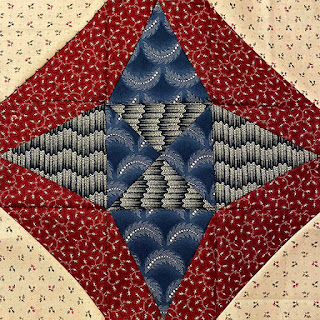

More honeybees here:Eby Byers & Catherine Byers

Chambersburg, Pennsylvania

1837

Honeybee by Georgann Eglinski

Further Reading

The Goodwin sisters' nephew kept a diary in which he mentioned their assistance to fugitives. Read

Diary of a Quaker Farmer by William Goodwin Woodnut.

And some links:

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Underground_Railroad_in_New_Jersey_and_N/CKjSCjMKhmYC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=goodwin https://www.google.com/books/edition/Past_and_Promise/h-6WCBQPZdoC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=abigail+goodwin+new+jersey&pg=PA65&printsec=frontcover

https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_and_Genealogy_of_Fenwick_s_Colon/njsVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=abigail+goodwin+new+jersey&pg=PA84&printsec=frontcover

https://blogs.stockton.edu/litrecovery2019/anne-walter-maylin/