Oh Boy! A Civil War quilt advertised on EBay.

I say Oh Boy! because it is a great opportunity to discuss why this is NOT from

the years of the Civil War (1861-65).

"Antique Civil War quilt. Hand sewn. Professionally cleaned and dated by textile expert. On point square in a square design appropriate to the period. Civil war squares date to 1864, joined with red and yellow fabric from 1877 to form the quilt top. Backing is also 1877. Note the two-color leaves, which were common to the era.""Dated by textile expert"

The best clues to quilt date are in the fabrics and the general style of pattern and set. The pattern here is a nine patch on point, what I've heard called a Diamond Nine Patch in the South. The patchwork pattern is not really a useable clue, though, too popular for too long. As the seller says it might be appropriate to the Civil War period, used in the 1860s, but also seen into the 20th century.

The backing or lining

The fabrics in colors and design are excellent clues to

date, however.

"Backing is also 1877. Note the two-color leaves, which were common to the era."

Those of us with experience with early-20th-century quilts will recognize the style of

this multicolored leaf print as what was called a "cretonne," a furnishing print, often seen on the

back of quilts from about 1890 to 1930.

"Civil war squares date to 1864, joined with red and yellow fabric

from 1877 to form the quilt top."

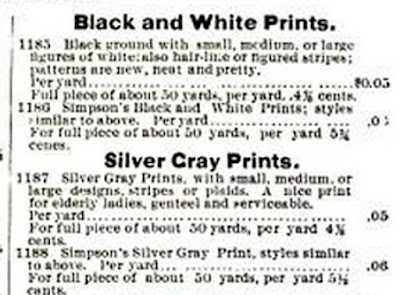

I'd describe this block as pieced from chambrays and shirting weaves, probably dyed with the synthetic indigo that created so much variety in colorfast, inexpensive blues from about 1890 on. The Nine Patch is set here into a black ground stripe, as described in this 1895 catalog from Montgomery Ward's. Cotton with true black was hard to obtain and one does not see it before 1890.

These black prints are one of the best clues to date in antique quilts. You can really count on them to date a quilt as after 1890 and into the 1930s.

1908 sample book

The triple strip border is what we might call a typical early-20th-century ditsy

or "bread & butter" print, the kind of inexpensive, nostalgic calicoes that were the

staple product of several mills.

I hope the seller didn't pay that textile expert too much to tell them the blocks dated to 1864 and the setting to 1877. I think what we have here is a quilt from about 1900 to 1930. Do note I give a range and not a specific year. Unless a quilt is dated you want to be accurate within a range of decades.

.jpg)