Cassandra's Circle #9 Lost Love for Buck Preston by Becky Brown

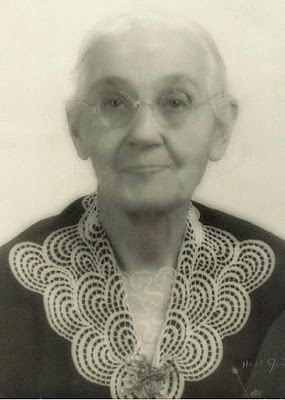

Sarah Campbell Buchanan Preston Lowdnes (1842-1880)

Known as Buck

Buck Preston was the star among the young women in Mary Chesnut's circle in Richmond and Columbia. "All men worship Buck. How can they help it, she is so lovely," wrote Mary.

Buck must have received dozens of proposals during the war when she was in her early twenties. But she was coy and kept many suitors on a string. Mary saw the cause of all the broken hearts. "Buck was never so decided in her 'Nos' as [sister Mamie]."

Buck,"who always reads what [Mary wrote in the diary], and makes comments of assent or dissent" wrote an amendment to this entry, claiming her "Nos" were "Not so loud, at least."

John Bell Hood (1831-1879)

Hood lost a leg and the use of one arm.

He spent recovery time in Mary's Richmond circle.

One of the men dangling on her string was Confederate General John Bell Hood from Kentucky. On seeing her in a pheasant feather hat the "blunt soldier [said] to the girl: 'You look mighty pretty in that hat...I surrendered at first sight'."

S.C. Preston

Mary was rather enamored of the unfortunate General herself:

"Hood with his sad Quixote face...tall, thin, and shy; has blue eyes and light hair; a tawny beard, and a vast amount of it, covering the lower part of his face, the whole appearance that of awkward strength....The fierce light of Hood's eyes I can never forget."

#9 Lost Love by Denniele Bohannon

Hood was terribly crippled by his injuries. “Buck can’t help it. She must flirt….She does not care for the man. It is sympathy with the wounded soldier. Helpless Hood.”

Mary records an incident when Buck gracefully assisted him in a crowd.

"The General was leaning against the wall, Buck standing guard by him...held out her arm to protect him from the rush. After they had all passed she handed him his crutches, and they, too, moved slowly away. [Varina] Davis said: 'Any woman in Richmond would have done the same joyfully, but few could do it so gracefully. Buck is made so conspicuous by her beauty, whatever she does can not fail to attract attention.' "

Mary kept a CDV portrait of Buck's father, friend John Smith Preston, in

her photo album. The pictures show Quinby's stage set in Charleston.

Lost Love by Pat Styring. She filled up the corners in her own fashion.

A few weeks after the war ended:

"Mrs. Huger says Buck has lost twenty pound[s]. since I last saw her & is a perfect wreck. Mrs P[reston] ought either to have broken her engagement or to have permitted the marriage. [Buck] rides with R. Lowndes."

Anna Marie Hennen Hood (1837-1879)

Buck and Hood married others after the war. Hood became a cotton broker in New Orleans where he wed Anna Marie Hennen a month after Buck's marriage in 1868. The Hoods had 11 children, including three sets of twins.

Composite picture of the Hood family in 1879.

Hood and his wife died in a yellow fever epidemic in 1879 leaving

ten orphans. P.T. Beauregard and other old friends used this photo to raise money

for their care.

Rawlins Lowndes (1838-1919)

Buck died the year after Hood in Charleston. She'd married a man of her own aristocratic class, planter Rawlins Lowndes in March, 1868. Rawly had been a wartime aide to her uncle General Wade Hampton.

The Caspar Shutt/Lowndes home

The Block

Everybody loved Buck so a heart is at the center of Block #9...

drawn from a friendship quilt top made in Cumberland County,

New Jersey

Offered in an online auction

The Pattern

One way to print these JPGS.

- Create a new empty JPG file that is 8-1/2" x 11" or a word file.

- Click on the image above.

- Right click on it and save it to your file.

- Print that file out 8-1/2" x 11". Note the inch square block for reference.

- Adjust the printed page size if necessary.

- Make templates.

- Add seams when cutting fabric.

For the star cut a square 17" and fold into quarters. Make a template of the pattern and

lay it on the folds. Add seams and cut.

The sprouting star is an unusual design but there are a few examples,

this one a block recorded by the New Jersey project and the Quilt Index.

Pat's corners with a triple fruit.

Minimalism in a quilt from about 1900

Pat Styring's Blocks 1-9.