Hospital Sketches #3

Virginia Cockscomb by Becky Brown

This flamboyant block recalls Robertson's Hospital in Richmond, a private facility that treated patients throughout the Civil War.

The hospital looked much like the white frame building on Main Street in this Alexander Gardner photo taken of the Confederate capitol during the war years.

Robertson Hospital was small--- 25 to 35 beds in a large house. The woman in charge, 28-year-old Sally Louisa Tompkins, is sometimes referred to as a Civil War nurse but she was what we'd call a hospital administrator.

After the war's first battle at Manassas Junction in July, 1861 Sally organized the women of St. James Episcopal Church in Richmond, found an abandoned mansion and went to work for five years treating over 1300 patients. Robertson Hospital, named after the home's last owner, dismissed their final patient in June, 1865.

Sally was proud of the hospital's mortality rate, much lower than other institutions large and small.

"Sally was almost obsessed with cleanliness. That obsession probably saved the lives of many in a time when the cause of infection was not understood...."

Frances H. Casstevens in Tales from the North and the South

She ran a tight ship on her own money.

Sally Louisa Tompkins

1833-1916

I Photoshopped a portrait from about the time the Civil War began

onto a quilt top attributed to her. The portrait is from the Virginia Historical Society,

the quilt from the Tompkins Cottage Museum in Mathews County, Virginia, taken by

Becky Foster Barnhardt.

Poplar Grove in Mathews County. Sally was born

in this plantation house passed on from her mother's family.

Diarist Mary Chesnut often visited Robertson Hospital in the first months of the war bringing food prepared by her slaves in Richmond and from her husband's family plantation in South Carolina. Southern hospitals were sometimes reserved for home state soldiers and Mary, perhaps thinking she'd favor Palmetto State boys, asked:

" 'Are there any Carolinians here?'

Miss T: 'I never ask where the sick and wounded come from.'

Mary: I was rebuked. I deserved it."

Virginia Cockscomb by Janet Perkins

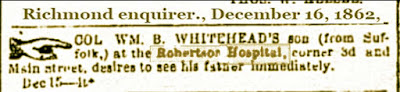

Hospital admissions were so chaotic people placed ads in

newspapers looking for relatives.

Chimborazo Hospital on a hill southeast of Richmond

was purpose built with small single-story wards.

Richmond had many hospitals ranging from the giant Confederate complex called Chimborazo that treated 76,000 patients during the War to smaller private hospitals like Sally's. The Confederate government discouraged private institutions but Sally's persisted, probably due to her connections and her competence.

In 1864 Sally advertised in the Richmond Dispatch for information about missing "servant boy Peter who has been employed for some time past as butler at Robertson Hospital." He might have run away or "been impressed by the Government officials," which might have been a common fate. It's hard to see how old he was but he was only 4 feet tall.

The Block

#3 Virginia Cockscomb

by Barbara Brackman

Three variations of the Cockscomb block in one quilt

We call it Cockscomb but in 1908 the Ladies Home Journal

called it The Olive Branch.

Quilts in the design were made long before 1908, and it seems

to have been particularly popular in Virginia.

For the background cut a square

18-1/2".

Add seam allowances to the pattern pieces if you are doing

traditional applique.

To Print:

Create a word file or a new empty JPG file.Click on the images above.

Right click on each and save to your file.

Print that file. Be sure the square is about 1" in size.

Album dated 1860 from the Steel and Ruth families for D.H.K. Dix

in Western Virginia, documented in the West Virginia project.

In 1860 Dix was a Methodist minister stationed in New Martinsville, Virginia.

See a post on the patttern here:

Subtraction

Sprouts #2

Sprouts is a version of the traditional pattern for the stitcher who

wants something quick. A separate quilt.

Sprouts 1 & 2 by Denniele

Sprouts #2

Denniele Bohannon

She is using a 9" finished background so has more room than the sketch below.

Cut a 9" square background.

Cut 1 A and 1 C and 4 B.

Cut 2 of leaf F from last months Periwinkle Wreath

You need a snippet of 1/2" finished bias for the stem.

After the War

Sally seated with unidentified women in the early 20th century.

Virginia Historical Society

After the war Sally Tompkins remained single, devoting herself to nursing in the more conventional sense of the word, caring for ill family members and friends. She was active in Richmond's Ladies' Hollywood Memorial Association and in funding the Home for Needy Confederate Women, where she lived for the last few years of her long life. After her death she continued to fund the institution. Women standing on street corners in Richmond sold "Sally Tompkins Buttons" in 1916.

The Robertson Hospital patients held a reunion in Richmond in 1896. See the register which is in the Library of Virginia.

Two quilts attributed to Sally from the

Tompkins Cottage Museum in Mathews County, Virginia.

Sally's coat at the Tompkins Cottage museum

http://www.lorijacksonblack.com/history-and-genealogy/captain-sally-louisa-tompkins-csa

See more about the pattern at these posts:

https://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2016/07/a-gawky-eagle-and-coxcomb.html

http://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2016/07/i-forgot-something-bird.html

Album made for Methodist minister D.H.K. Dix

West Virginia project & the Quilt Index

https://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2016/07/a-gawky-eagle-and-coxcomb.html

Women and children among the ruins of Richmond after the war

Virginia Cockscomb by Bettina Havig

Lorraine asked for a plan and that's a good idea so I've added a diagram of my quilt with blocks 1 & 2. Block 1 (non-directional) goes in the center. Block 2 (diagonal) goes in a corner. Could point in or out. The north/south axis blocks are not directional.