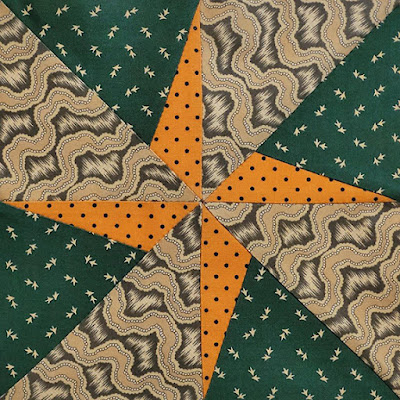

American Stars #3 Double Pinwheels by Becky Brown

Double Pinwheels recalls the Gratz family, North and South, and their double heritage.

Rebecca Gratz (1781-1869)

Miniature on ivory by Edward Greene Malbone

American Jewish Archive

In her long life Rebecca Gratz wrote many letters, giving us much information about her distinguished Philadelphia family whom, we are happy to say, saved their papers.

Sully family portraits of Miriam Simon (1750-1808)

& Michael Gratz (1740-1811), Rebecca's parents.

Her father Michael Gratz was a Philadelphia merchant, born in Silesia and educated in London, who emigrated with his brothers to the colonies in the 1750s. He and Miriam had eight children, four girls and four boys. Three of the children married but Rebecca, Sarah and three brothers remained single, spending their lives together in the family home, moving as economic circumstances changed.

The Gratzes apparently lived in this building at 7th & Market Streets in the early 19th century. The house was torn down but has been reconstructed because Thomas Jefferson boarded here while he wrote the Declaration of Independence.

Rachel Gratz Moses by Gilbert Stuart

The Rosenbach Library has a collection of Gratz portraits.

When sister Rachel Gratz Moses died in 1823 leaving young children their aunts and uncles took over much of their care.

See a post on one niece Miriam Moses Cohen's quilt here:https://civilwarquilts.blogspot.com/2022/02/miriam-moses-cohens-civil-war.html

The brothers, rich men all, have left no mysteries about their bachelorhood but Rebecca Gratz has too often been defined by her chosen spinsterhood. As wealthy heirs she and sister Sarah did not need husbands to support them.

The story that has been perpetuated since 1820 (when Rebecca was in her forties): This Jewish woman was in love with a Gentile but believing strongly that Jews should not marry outside their faith she rejected her true love. The tale really has little basis. Beautiful and wealthy she had many suitors but chose to live an independent life in the company of her brothers and her "children"---her nieces and nephews.

Rebecca has long been linked to the the Rebecca in Walter Scott's

romance Ivanhoe, the Jewish woman who refused to marry Ivanhoe

because of her religion.

1932 article in the Kansas City Star. The myth continues today.

#3 Double Pinwheels by Denniele Bohannon

Benjamin Gratz ( 1792-1894) by Thomas Sully

Brother Benjamin did marry outside the faith. The youngest of Michael and Miriam's children was sent west after the War of 1812 to manage family enterprises in Kentucky. Settling in Lexington he created a southern branch of the family, becoming a Southerner in many ways. He made his own fortune, first in manufacturing rope, then in railroads. Creating rope from hemp was tough manual labor. At one point Benjamin had 75 slaves working in this profitable enterprise.

The census's 1850 slave schedule lists 61 unnamed people on this page

and probably more on the next for Benj. Gratz.

Maria Gist Gratz (1795-1841) by Lexington artist Matthew Harris Jewett.

Maria, a native Kentuckian and an Episcopalian,

was Benjamin's first wife, married in 1819.

With skills at creating relationships and a tight family web, Rebecca befriended her new sister-in-law. Her letters to Maria detailing events in the Philadelphia household have been published. The extended family mourned when Maria died in her mid forties. Benjamin married his late wife's niece Anna Maria Boswell Shelby in a year or two. She was a rich widow; owner of 28 slaves according to a family account. Benjamin brought four adolescent boys to the marriage; Ann had one, Joseph Orville Shelby in his mid teens.

The Block

The block Double Pinwheel Whirls was published in Quilters' Newsletter a few decades ago,

a rather modern looking star. It's #1267 in BlockBase+.

Print the pattern on an 8-1/2 x11" sheet of paper.

Note the inch square for scale.

#3 Double Pinwheels by Jeanne Arnieri

Jeanne added an extra strip.

The Next Generation

Mount Hope, the family home, still stands at

Mill & New Streets in Lexington's Gratz Park

The Lexington Gratzes welcomed family and neighbors at Mount Hope. Among the young students who lived at their home close to Transylvania University were cousins Frank Blair and Benjamin Gratz Brown. When the boys visited the Philadelphia Gratzes Rebecca wrote sister-in law-Ann complimenting her son: "Jo seems to have the spirit of mirth inborn in him."

A tight family but civil war created divisions.

Rebecca in her seventies in the 1850s

At graduation the Lexington cousins headed for St. Louis about 1850, some to practice law and later politics. Henry Gratz and half-brother Jo Shelby were in search of their own fortune in the rope business and perhaps a western life free of parental supervision. Rebecca, fond of her nephew Jo, was optimistic.

"So amiable affectionate & clever....he has gone to such a thriving place and where he has so many friends!"

Henry eventually returned to Kentucky in 1856 where he became a post-Civil-War newspaper editor, but Jo took to the Missouri frontier, settling in Waverly on the Missouri River about 75 miles from the state's western border with the new Kansas Territory. Their Waverly Steam Rope company required slave labor (reportedly 50 slave workers) and he became committed to the proslavery cause as Missourians defined it.

State Historical Society of Missouri

Joseph O. Shelby (1830-1897) in 1857

Shelby's Missouri career is romanticized by nostalgic Southerners

In his mid-20s, he came under the influence of Claiborne Jackson and David Rice Atchison, proslavery politicians advocating fraudulent voting in elections determining whether Kansas would be a free or slave state. Law-breaking escalated into terrorism and guerilla attacks on free-state settlers across the state border.

Missourians attack Lawrence, Kansas, 1856

Years later Shelby told Kansas historian William Elsey Connelly who quoted him in his book Quantrill & the Border Wars:

"I was in Kansas at the head of an armed force [in 1863]....I went there to kill Free State men. I did kill them. I am now ashamed...but then times were different....Those were the days when slavery was in the balance and the violence engendered made men irresponsible."

So it was circumstances that drove him to murder.

After Fort Sumter in 1861 Rebecca in Philadelphia worried about Ann's son: "What is the position of Jo Shelby in this terrible struggle? Missouri seem to be most turbulent." His position: A continuing commitment to slavery and violence to protect it. He organized a Confederate brigade in Union Missouri.

General Joseph O. Shelby

University of Kentucky Library

"I have seen [Jo's] name mentioned in the Southern Army...We may pray for Jos personal safety-tho' we cannot for the success of his arms." Aunt Rebecca.

The rest of the Gratz family remained Union loyalists, including Benjamin's son Cary Gratz who was killed early in the war in a Missouri battle with him and his step-brother on opposite sides. Lexington neighbor John Hunt Morgan also chose the Confederacy. He married Rebecca Gratz Bruce,

a family namesake if not a relative.

Rebecca Gratz Bruce Morgan ( 1830-1861) died of

complications from childbirth.

John Hunt Morgan (1825-1864)

Boyhood friends Morgan and Shelby developed Confederate swagger

that created a long romantic reputation.

Jo Shelby must have been a charismatic charmer (glorified today despite his traitorous behavior.) His Union family continued to speak well of him and help him out. When Missouri became a nightmare of guerilla war in 1863, Benjamin Gratz traveled to Waverly to escort Jo's wife and children back to the safety of Lexington, Kentucky. After Confederate defeat Jo Shelby refused to accept reality and took his family to Mexico, although that plan did not live up to his expectations either.

Among the Lexington cousins who'd moved to Missouri in 1849 were Frank Blair and Benjamin Gratz Brown, lukewarm free-state supporters who became Union leaders during the war. Brown, who went by the name Gratz Brown, ran for American vice-president after the war as Horace Greeley's unsuccessful running mate.

Anna Maria Boswell Shelby Gratz (1808-1892) at Mount Hope

Family solidarity deteriorated as younger family members grew up. When Ann Shelby Gratz died in 1892 her will left most of her ($40,000-$100,000?) estate to her surviving Lexington daughter Anna Gratz Clay and $4,000 to each of her four grandchildren. Joseph Shelby received only a small bequest.

He sued to overturn the will, supported by his nieces and nephew, accusing his sister Ann Gratz Clay of undue influence on their mother.

Cincinnati Enquirer, March 1, 1895

If you want to read more "spicy testimony" or spiteful testimony do a newspaper search in February & March, 1895 for family names like Annie Gratz Clay and Jo Shelby.

It turns out (if you believe Shelby's lawyer) that no one in the family liked sister Ann Gratz Clay (Mrs. Thomas Hart Clay, Jr.) Dubious documents were introduced and rejected. The lawyers came close to fisticuffs; the family's feud was spread over the newspapers. Shelby lost.

It was those bigoted Union veterans on the jury, Jo told the pro-Confederate

Kansas City Times, one of the Kansas City papers

that did a great deal to make his legend.

Denniele's block as an all-over repeat.

Further Reading:

1 comment:

I loved that you were able to trace through the generations here. It makes the history so alive.

Post a Comment