Right Hand of Friendship

By Becky Brown

Right Hand of Friendship can remind us of the networks of help that continued to form an "Underground Railroad" throughout the Civil War.

While slavery's foundations began to crumble in 1861, the system continued in most places until the War was over in 1865. Near St. Louis, Missouri, a border state that never joined the Confederacy, Archer Alexander and his family lived in slavery through much of the War.

His slave-holding neighbors helped the Confederate cause in small ways by burning bridges to confound Federal patrols. When he heard of a planned bridge attack, Archer impulsively ran to a Union neighbor's home with information. Realizing the consequences his spying would earn him, he kept running---into the city of St. Louis where he was fortunate to meet the family of William Greenleaf Eliot, a Unitarian minister with abolitionist sympathies. Eliot agreed to hire him and offered to buy his freedom and that of his wife Louisa, left at home with no idea of what had happened to Archer.

William Greenleaf Eliot,

a friend to many slaves.

Louisa received a welcome letter assuring her of her husband's safety and the generous offer of freedom, but had to dictate a sad reply:

"MY DEAR HUSBAND,--I received your letter yesterday, and lost no time in asking Mr. Jim if he would sell me, and what he would take for me. He flew at me, and said I would never get free only at the point of the Baynot, and there was no use in my ever speaking to him any more about it. I don't see how I can ever get away except you get soldiers to take me from the house, as he is watching me night and day. If I can get away I will, but the people here are all afraid to take me away. He is always abusing Lincoln Lincoln

Archer, the Eliots and the Louisa's neighbors formed new plans. The Eliots offered to shelter Louisa and daughter Nellie. A neighbor agreed to carry them in his oxcart to the city for payment of $20. Clad only in day dresses without bonnets or shawls so as not to raise suspicion they were planning to travel, Louisa and Nellie sauntered to the road near their cabin where they'd agreed to rendezvous. The farmer hid them under the cornshucks in the wagon and casually walked along, leading his oxen to the city as farmers did every day. Despite questioning by suspicious locals, the escape was a success.

Letters sent by the U.S. Post Office during the War looked much like ours today

with envelopes, 3 cent cancelled stamps and a date cancellation.

Louisa and Archer could not read or write, yet they managed to carry out a complex plan by mail. We often think of illiterate people as being deprived of any written communication (a possible reason for all the stories about secret visual codes in tales of slavery) but we should realize many social systems were in place to assist those who needed help. In Louisa's case sympathetic neighbors took dictation and carried their correspondence, acting as an informal and illegal post office.

Archer Alexander so impressed William Eliot that the minister wrote his story as a legacy for the Eliot grandchildren, hoping to keep the story of slavery alive for future generations. Eliot eventually published the account in the 1880s. William Eliot's school, the Eliot Seminary, became Washington University

Archer, a handsome man into his old age, became the model for sculptor Thomas Ball who had a commission from former slaves to create a statue of Lincoln

Today that image rankles. Archer seems to symbolize passivity, a man waiting to be rescued. But it is important to recall that the kneeling slave had great meaning for blacks and whites during his life time. The man in shackles signified both a sympathy for the slaves' plight and a willingness to act.

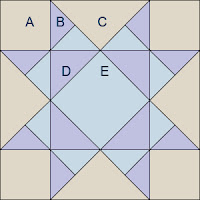

The quilt block Right Hand of Friendship was published by Hearth and Home magazine in the early 20th century. It is BlockBase #2831.

Cutting an 8" Finished Block

A Cut 4 background squares 3-1/8".

B Cut 1 background, 1 dark and 1 medium square 3-7/8". Cut each into 4 triangles with two diagonal cuts. You need 4 of each.

C Cut 1 dark and 1 medium square 3-1/2". Cut each into 2 triangles with one diagonal cut. You need 2 of each.

Read William Greenleaf Eliot's book: The Story of Archer Alexander: From Slavery to Freedom at the Documents of the American South webpage.