The Armory Square hospital in Civil War Washington was innovative and well-run.

A correspondent for the Portland (Maine) Press described it as exceptional, "the best

conducted hospital in the city." Credit was due Doctor Doctor Willard Bliss, the Surgeon in Charge.

That's not a typo. Dr. Bliss's first name was Doctor.

Each of the 11 wards was served by a "Volunteer Lady Nurse."

Amanda Akin Stearns published a memoir in 1909,

The Lady Nurse of Ward E with photos of

her fellow workers.

Amanda Akin (lower left) S. Ellen Marsh of Ward G at the top

& Nancy Maria Hill of Ward F.

Ira Spar has written a history of the hospital newspapers published

by staff and patients, in which he mentions a donation to Armory Square:

"Mrs. A. Fogg of Maine sent a 'loaner gift' of a quilt flag in red, white and blue to aid a soldier on Ward F...The white stripes had patriotic sentences and lines of poetry."

It is possible the the paper's volunteer proofreader failed to catch the typo in Mrs. Fogg's first name. I would guess we are referring to Isabella Morrison Fogg of Calais, Maine, who worked with the Maine Camp and Hospital Association and later the Christian Commission.

Maine State Archives

Isabella Morrison Fogg (1823-1873)

Like this?

Inscription in white stripes on a flag quilt in the collection of the Belfast (Maine) Historical Society.

The lines give us information on the 23 makers who belonged

to the First Church's Ladies' Aid Society.

A little humor punning on Generals' names:

"The right side, Our side and Burnside."

"A hard resting place for the rebels – General Pillow”

And some cheerleading:

"Hurrah for the Boys of the Pine Tree State"

Belfast's First Church, a Congregational Church remodeled by

the time of this early 20th-century photo. Notice the connected

structures so typical of northern New England architecture.

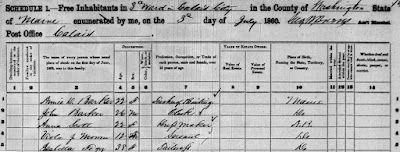

The 1860 Calais census shows Canadian-born tailoress Isabella Fogg living with the

Barker family and two other young Canadian natives.

Isabella Fogg, a widow when the war began, had supported herself and her son as a "tailoress." As a professional seamstress she might have organized or stitched the flag quilt mentioned in the newspaper, but it seems likely she just delivered this gift from Maine quiltmakers to the hospital.

Dr. D. Willard Bliss (1825-1889)

When the war was over Dr. Bliss took custody of the Belfast ladies' quilt. It went to his daughter

Eugenie Prentiss Bliss Milburn who moved with her husband to Miles City, Montana. The quilt was almost destroyed in Montana but was rescued by the Rickl family who donated it to the Belfast Museum.

Like the quilt, Dr. Bliss and Isabella Fogg were not fortunate after the war. Willard Bliss attended to two assassinated Presidents, both of whom were his friends: Abraham Lincoln in 1865 and James Garfield in 1881. Neither survived but no one blamed Dr. Bliss for Lincoln's death. However, Garfield's awful death from gangrene after 80 days was attributed to Bliss's bungling. The doctor died in disgrace a few years later.

Bliss was only one of at least six doctors trying to save Garfield.

True, he appears to have been quite didactic and a bit of a bully.

Perhaps at 56 he was not at the height of his powers.

But people remembered what a good job he did during the war.

Defense of Dr. Bliss by Mrs. H.C. Ingersoll, who worked at

his Civil War hospital and edited the newspaper there.

Isabella Fogg, working on a hospital ship towards the end of the war, fell through a deck hatch seriously injuring her spine. She spent two years in bed recovering and was incapacitated enough to be granted a pension for her war injuries two years later. She is sometimes credited as the first woman to receive a Civil War pension.

I'm always wary of claims to "only" or "first, words used by lazy history writers to describe the past. Although credited as the first and the only etc. Isabella Fogg was one of many women to be granted a pension. Here on the last day of February, 1867, Congress increased it.

"When the quilt was finished and ready for the quilting we were invited to the house of Hon. N. Abbott and a picnic supper was served, to which the young men were invited. The quilt was finished during the afternoon, and was displayed in the dining room and was much admired. The following week it was sent to Washington by express, accompanied by a letter from our President Miss Arbella Johnson."Augusta S. Quimby Frederick's Memoir

Augusta Susan Quimby (1833-1928) the year the war began.

Further Reading:

Links:

2 comments:

Wasn't it common for a married woman to go by her husband's first name? Was Isabella Fogg's husband "A" someone? I wonder if the Armory Hospital had some government support and so was in better shape. The flag is beautiful.

Sue I thought of that just before it went up today. I wonder what her husband's name was.

Post a Comment