Civil War New York City was the center of the North's commercial life. As we are interested in dry goods --- fabric--- we can look at Fredericka Wiesener Mandelbaum (1825-1894) who ran a thriving fabric business south of Houston Street on the Lower East Side in a neighborhood then called Kleindeutschland, or Little Germany.

Fredericka was born in Hesse-Kassel, a German principality. As a Jew she and her family undoubtedly were affected by their outsider status.

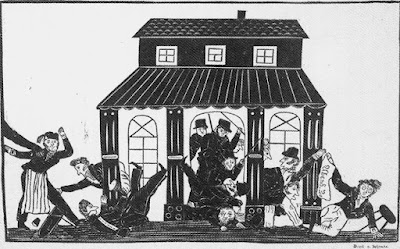

German Anti-Jewish riot, 1835

Fredericka married German Wolf Israel Mandelbaum. In 1848, the Year of Revolutions when political instability encouraged thousands of German immigrants to the United States, the Mandelbaums arrived in New York City and like thousands of Germans settled into the Lower East side.

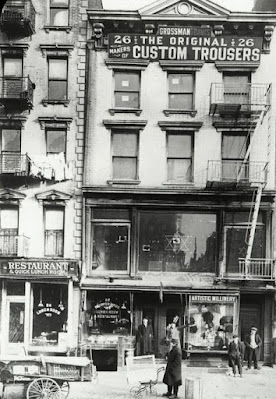

Library of Congress, about 1909

Their neighborhood on Rivington Street was the heart of commerce

in the immigrant neighborhood.

The Mandelbaums earned a living as street peddlers but worked their way up to establishing a store, which flourished.

Family Search

Wolf (whose name is occasionally Americanized to William)

was naturalized in 1856

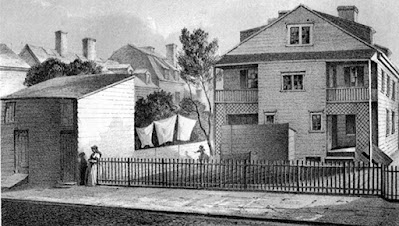

New York Public Library

Tailoring and millinery shops on Rivington Street

early 20th century.

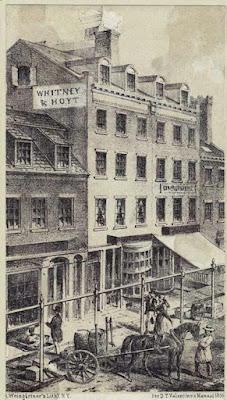

1860s SoHo

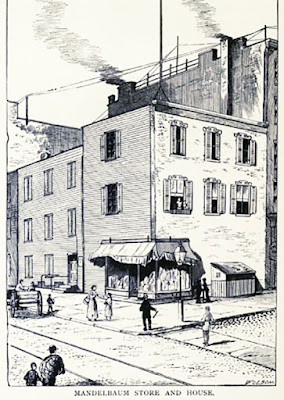

Photos of Lower East Side commerce date 40 years or more after the Civil War. The 5-story buildings were after Fredericka's time. Her dry goods store was at the corner of Clinton & Rivington Streets

and extended into two adjacent houses on Clinton.

From Recollections of a New York Chief of Police

by George W. Walling, 1887

Library of Congress

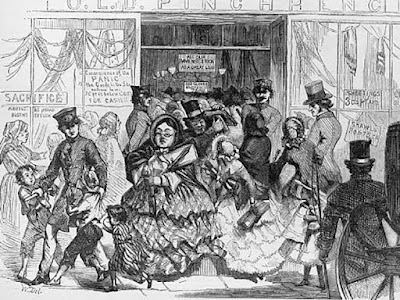

Dry goods store in New York, 1857

When the Civil War began Fredericka was mother to baby Julius born in 1860. She gave birth to Sarah in 1863, eventually having two boys and two girls. Youngest Anna was born in 1867.

London dry goods shops by George Cruikshank

Now, do not think the frequently pregnant Fredericka was running a conventional dry goods store (whatever conventional was in 1861.) Apparently she and Wolf made a huge amount of money as "fences" for stolen goods, particularly stolen silk yardage.

1863 New York Times

An honest (?) silk dealer in New York advertised silks at $6 while cotton

dress goods were 30 cents a yard.

Their business model was brilliant (if unlawful.) Unlike jewelry, which they also fenced, fabric yardage was was hard to connect to its rightful owner. With silk at $6 a yard during wartime shortages a ten-yard bolt could finance a rather luxurious life style (and police pay-offs.)

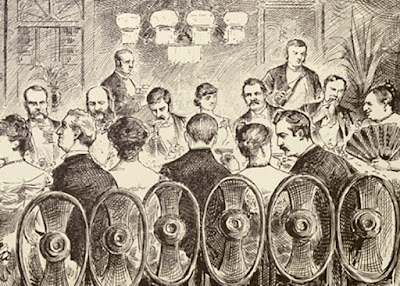

Fredericka at work

She was, shall we say, a heavy-set woman, supposedly 6 feet tall.

She's usually depicted in a Jewish-stereotypical caricature as in this

imaginary view of a dinner party she hosted in her elegant

dining room on Clinton Street.

Fredericka was finally arrested and tried for selling stolen goods in 1884. By then Wolf had died. She was indignant in the press:

“I keep a dry goods store, and have for twenty years past. I buy and sell dry goods as other dry goods people do. I have never knowingly bought stolen goods. Neither did my son Julius. I have never stolen anything in my life. I feel that these charges are brought against me for spite. I have never bribed the police, nor had their protection."

And she got plenty of press.

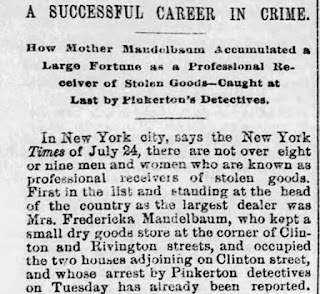

1884, Lancaster Pennsylvania Gazette

Her downfall came in the era of sensational news items so any facts lurking behind the journalism are hard to ferret out. Everyone involved in her arrest had some motive for publicizing the case, from the Pinkerton Detectives who picked her up to NYC Police Chief George Washington Walling, who wrote about her in his memoirs. She was

nicknamed Marm or Mother Mandelbaum in the press where columns of her exploits were published.

Puck cartoon by Joseph Keppler about vaccinations for criminals

featuring Marm Mandelbaum

The newspaper accounts were also fueled by the antisemitism

increasing with increased immigration. Her whole reputation as

the biggest receiver of stolen goods in the country appears to be

extremely exaggerated.

Was she dishonest? Undoubtedly. Fredericka protested her innocence but jumped bond and took her

children to Ontario, Canada where she remained until her death in 1894.

Keppler & Puck

It's hard to view the Mandelbaum dry goods business beyond the sensationalism, but it does give one insight into how wartime fabric shortages can inspire innovation in the dry goods business.

Purported fellow crook Sophie Lyons wrote a book with memories of Mandelbaum in 1913. See a preview of Why Crime Does Not Pay:

3 comments:

What a character! (As my mother would say.)

Thank you for sharing. That was very interesting.

Γεια, διαβάζοντας για την ιστορία της Marm Mandelbaum και τις εφημερίδες που υπερβολικά μετέφεραν τα γεγονότα μου θύμισε πώς κι εγώ ψάχνω τρόπους να χαλαρώνω και να ξεφεύγω από περίπλοκες ή βαριές ιστορίες εδώ στη Γελλάδα. Πρόσφατα δοκίμασα το spin mama casino που μου σύστησε ένας φίλος για λίγη διασκέδαση και παιχνίδι. Ξεκίνησα με το Sweet Bonanza και στην αρχή δεν είχα τύχη, αλλά μετά από λίγο ήρθε μια ξαφνική σειρά κερδών που πραγματικά με έφτιαξε τη διάθεση και με έκανε να νιώσω χαλάρωση. Τώρα το χρησιμοποιώ για μικρές στιγμές παιχνιδιού και ανάπαυλας όταν θέλω να ξεφύγω από περίπλοκες ιστορίες και ειδήσεις.

Post a Comment