Atlanta Garden #6: The Hand of War by

Jeanne Arnieri

General William Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1891)

from the Brady Studios, 1864

According to Atlanta's Intelligencer: "The barbarous chief of barbarian hordes."

Although painted as a rampaging villain in Lost Cause narratives recalling the Southerners' war, Sherman knew the consequence of his invasion in the summer and fall of 1864. Each step was planned and defended articulately.

“We are not only fighting armies but a hostile people, and must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war.”

The Hand of War by Denniele Bohannon

Sherman, who'd once lived in Georgia, gave much thought to his Atlanta strategy. He knew the country; he knew the city's importance to the Confederacy's supply lines.

"All that has gone on before is mere skirmishing---The War now begins.” Sherman to his wife before taking Atlanta.

Sherman (right) leaning on a Parrott cannon

used to shell Atlanta. Batteries were stationed north and west of town.

Sherman's order: "Fire slowly and with deliberation between 4 p.m. and dusk."

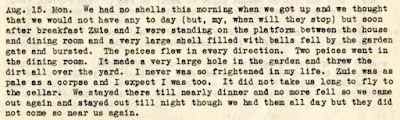

Carrie's diary for August 15, 1864, transcript from the Atlanta History Center

The shelling's purpose was to convince Atlantans to abandon the city and to demoralize those remaining (except perhaps slaves hoping for deliverance and Unionists like the Berry/Markham/Healey family.)

Unionist Cyrena Stone was in her garden in May, 1864 when she heard Union cannon in the distance: “O that music….Never fell on my ear any sound half so sweet.”

The Hand of War by Becky Collis

Carrie Berry experienced Sherman's assault nightly as did Sam Richards, worried more about his shop's inventory than his safety.

"Sallie and I walked out Marietta street this morning to see the devastation caused by the bombardment, and truly that part of the city is badly cut up." Sam Richards, August 29, 1864.

At the same time destruction of rail lines outside Atlanta rendered the city useless as a Confederate source for munitions and weapons. Die-hard residents were in danger of starvation as supplies were halted. General Hood pulled all Southern troops out of the city on September 2, leaving it open to Union occupation.

Confederate General John Bell Hood (1831-1879), Brady Studios

Buildings & tracks in the Western & Atlantic Railroad yards,

the line founded by Carrie Berry's family. This roundhouse

was near their home.

Hood had given responsibility for moving a trainload of ammunition and armaments out of Atlanta but despite repeated instructions his quartermaster, Colonel M. B. McMicken failed to act.

"He had more than ample time to remove the whole.... I am reliably informed that he is too much addicted to drink of late to attend to his duties." General John Bell Hood, September 4, 1864.

Hood realized it was too late to move those railroad cars stuck on tracks near the Iron Mill and the Atlanta Machine Company. Rather than leave the armaments to Sherman's Army, Hood ordered the cars burned.

Jeanne Arnieri's second set of blocks.

The Rolling Mill, a combustible factory, was adjacent

to the tracks.

"The Ammunition Train was fired and for half an hour or more an incessant discharge was kept up that jarred the ground and broke the glass in the windows around." First person account: September 1

The fictional Rhett Butler and Scarlett O'Hara leaving the burning city

Well, Margaret Mitchell will tell you what happened next. One of the most memorable scenes in movie history is Gone With the Wind's burning of Atlanta after Hood ordered the munitions cars destroyed. The explosions set the factories (and a good deal of the neighborhood) afire. Neighbors had been warned to leave.

The Hand of War by Becky Brown

The Markhams' Rolling Mill as it appeared when Union armies

entered the city. The only remains of the box cars were wheels and axles.

Carrie's account of the Confederates burning the box cars

Despite all the eye-witness accounts, local Atlanta history too often remembers that it was Sherman not Hood who blew up the train and the Markham factory. Here is a paragraph from Franklin Garrett's mid-20th-century history Atlanta and Environs

The Block

BlockBase #1879, about 1880-1900

A bird's foot, a cat's paw or a human hand?

Pennsylvania-German quiltmakers called the pattern

Batsche, a reference to hands. Ruth Finley in 1929 published the nine-patch as Hand of Friendship but for Carrie Berry in Atlanta it can stand for the hard Hand of War.

The Hand of War by Addie

Above the cutting

instructions for 10" and 15" blocks.

About 1910

.jpg)

1 comment:

A History lesson & a quilt block,can't get any better than that! I luv reading the History attached to this block

Post a Comment