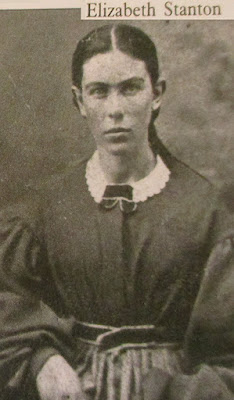

Elizabeth Stanton, Barnesville, Ohio

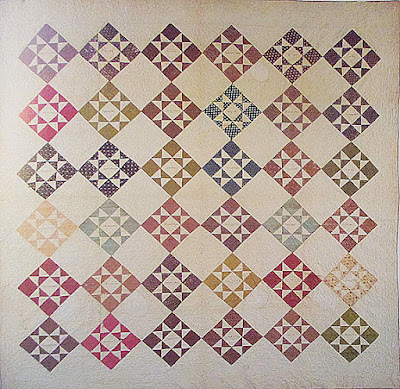

"Lizzie/Stanton/Barnesville/Ohio/1865" inked in an unpieced central

block in an album quilt with dates from 1856 to 1865.

https://quiltindex.org//view/?type=page&kid=35-90-368

When the Civil War began in April, 1861 Nettie Flanner was again living in the Quaker community of Mount Pleasant having recently returned under trying circumstances from four years in Missouri. She and her idealistic husband Henry Beeson Flanner (1823–1863) brought their 7 children back to Mount Pleasant after being driven out of Missouri by Southern extremists who threatened to tar and feather him for his pro-Lincoln sentiments in the fall 1860 election.

Nettie's father died in 1860, adding to her woes. The Missouri experience was undoubtedly emotionally devastating but they also lost their real estate investment there. Daughter Anna Flanner Buchanan recalled that neighbors in Mount Pleasant lost any respect for them believing Henry had "squandered [his money] on a fool's errand...a hair-brained mission in Missouri....[Nettie] was always greatly embittered" by their treatment in Mount Pleasant.

The widowed Nettie was glad to leave Mount Pleasant for Indianapolis where she'd gone to boarding school and family remained. She took her five younger children, hoping to become a teacher of botany and music but she settled for running a boarding house.

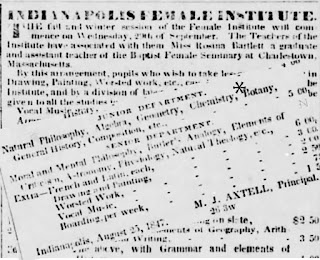

The Flanner women were bright, independent and a bit eccentric. Nettie had attended the Indianapolis Female Institute, a Presbyterian school run by Mary J. and Harriet Axtell of New York where history, mathematics and natural history were part of the curriculum.

Brenda Wineapple's, Genet, a biography of Janet Flanner, contains much information about her Flanner ancestors. Wineapple referred to a few unpublished manuscript collections, among them Henry Beeson Flanner's diary, 1856. Western History Manuscript Collection. State Historical Society of Missouri Manuscripts. University of Missouri, Rolla.

Elizabeth Stanton (Bailey) (1846-1936)

The quilt was also pictured in Quilts in Community:

Ohio's Traditions (page 133).

Barnesville and Mount Pleasant (the star) are in adjacent counties

She connected many of the names to Lizzie's relatives and found that some of the younger women had been fellow students at Ohio's Mount Pleasant Quaker Boarding School near Barnesville.

She also gives us a picture of religious and social conflicts in mid-19th-century Quaker communities. Another resident of Mount Pleasant tells us more about the town in her story.

Orpha Annette "Nettie" Tyler Flanner (1824–1914)

Photo from her FindaGrave file:

Orpha Annette lived in Pennsylvania, possibly New York & North Carolina,

spent her years before her 1845 marriage in Indiana, then moved with her new

husband to Mount Pleasant, Ohio.

After buying 600 acres near Lake Spring and Rolla, Missouri, Henry had brought his wife, six children (youngest Anna Phoebe was born in Missouri) and his 84-year-old Aunt Annie who'd raised him. With an idea of opening a school to teach his principles he'd taught at Lake Springs' Union Independent Academy for a short time.

Lake Springs, Missouri in Dent County

Brenda Wineapple who's written a biography of Nettie's famous granddaughter, New Yorker correspondent Janet Tyler Flanner, tells us that Henry wrote to his father:

"As Lincoln's election approached, days of troubles came! Free state men...were run off....We could not sell, trade, or do anything but leave....We all escaped with our Lives! nothing more."

Nettie's father died in 1860, adding to her woes. The Missouri experience was undoubtedly emotionally devastating but they also lost their real estate investment there. Daughter Anna Flanner Buchanan recalled that neighbors in Mount Pleasant lost any respect for them believing Henry had "squandered [his money] on a fool's errand...a hair-brained mission in Missouri....[Nettie] was always greatly embittered" by their treatment in Mount Pleasant.

Mount Pleasant's Free Labor Store, shunning slave-produced goods.

Nettie, not a Quaker, was shunned as was Henry for marrying

outside the faith.

Although a Quaker, Henry saw an opportunity to support the family by enlisting as a substitute in the 113th Ohio Infantry, hoping to be a noncombatant bandmaster. But musicians caught diseases and within a few months he was seriously ill with swollen legs and a cough. Sent home, he died in May, 1863.

Indianapolis about the time the Flanners arrived

During the ten years the Axtell sisters ran the school

students learned a good deal of Botany and Natural History,

inspiring Nettie to become a life-long botanist.

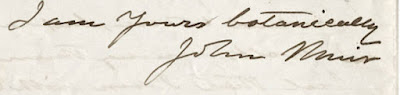

Henry and Nettie shared a love of botany as shown in this letter

in the collection of the Indiana Historical Society.

"My wife is also a Botanist....We call our Eldest Linnaeus" for

the famous taxonomist.

1867 letter from John Muir

Nettie must have found a good deal of consolation in her botany collections and her correspondence trading specimens with other amateur and professional scientists. The Historical Society also has her correspondence with John Muir.

At one point in an 1872 religious fever she "declared her herbarium a product of sin," having broken the Sabbath Sundays to look for plants, according to Brenda Wineapple. Nettie did hold on to the 15,000 specimens, however, and in 1889 donated the collection to Ohio's Marietta College.

1889 Indianapolis News

Further Reading

Ricky Clark, George W Knepper & Ellice Ronsheim, Quilts in Community: Ohio's Traditions

Janet Flanner's father, Nettie's son Frank was also bright, independent and eccentric. Read a little about him here:

1 comment:

Really interesting! I wish I could have known her, especially because some people refer to me as being "slightly eccentric" too!

Post a Comment