Block #10 Kansa Star for the Papins & Gonvilles by Becky Brown

This portrait of a Kansa man, known in English as White Plume (1760s -1838), hangs in a library at the White House. He's wearing a silver medal with an image of President James Monroe.Nom-pa-wa-rah (his name in Kansa) had traveled to Washington in 1821 at the invitation of President Monroe's administration who wanted assurances the Kansa tribe would pose no threat to travelers on the trail down to Santa Fe in newly independent Mexico. Three years later Nom-pa-wa-rah, considered the chief of his tribe, was the first signer of twelve Kansa men on a treaty to cede the land that would become the Kansas Territory.

Gallery of Portraits by King in the Smithsonian

While he was in the East Nom-pa-wa-rah was painted by Charles Bird King in a project to depict Native visitors. His portrait above was one of the few to survive an 1865 fire at the Smithsonian.

Another painter George Catlin visited the Kansa in the 1830s, describing the elderly Nom-pa-wa-rah as "an urbane and hospitable man, of good portly size, speaking some English and making himself good company." Catlin, unfortunately, did not paint him.

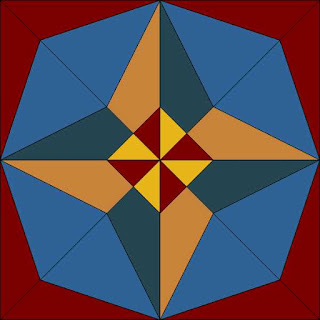

Kansa Star by Denniele Bohannon

White Plume must have been a practical man, watching American/European settlement creep westward as Missouri only 50 miles from his home became a state in 1820. In the 1825 treaty he and the other Kansa leaders secured land for their offspring, White Plume's being listed in the treaty as Josette, Julie, Pelagie and Victoire, his four granddaughters. Each girl got a mile-square reservation across the Kansas River from what would become Topeka.

"Half-Breed Lands" in blue from an 1856 map of Kansas

About half the mixed-blood children were females, land owners

at a time when married white women often had to cede their

real estate to their husbands.

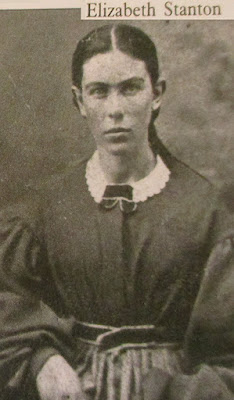

Julie Gonville Papin (1811-1896)

We'll follow one branch of Nom-pa-wa-rah's family, granddaughter Julie who'd owned a square mile on the Kansas River since she was in her mid-teens. Her grandmother was Wyhesee, an Osage woman who partnered with Nom-pa-wa-rah.

Julie's father Louis Gonville had come to the Kansa land from St. Louis, one of the many French and French Canadians seeking a fortune in fur trading. He was never a successful trader like the Chouteaus for whom he worked as a farmer and translator at their trading post but he was described by Frederick Chouteau as "a very good man you could depend on," married to Hunt-Jimmy. About 1818 Gonville married Hunt-Jimmy's sister Wyhesee. Whether Hunt-Jimmy had died or Gonville had two wives we do not know. Four girls by two Gonville wives survived to come matriarchs on the north side of the Kansas River.

The Kansas or Kaw River

Julie herself married a Frenchman from St. Louis, fur-trader Louis Papin (Pappan) (1785-1852) who came with his three brothers to the Kansa land.

Family Search

An April, 1855 marriage certificate for Julie Gonvil and Louie Pappan,

probably formalizing an older relationship for the new

Kansas Territorial government.

Brothers Louis, Ahcan and Euberie Papin married sisters Josette, Julie and Victoire Gonville.

Marie Louise Chouteau & Joseph Papin,

Julie's French Canadian parents-in-law from St. Louis

Missouri Historical Society

Julie and Louis had 12 children and her sisters were probably equally fertile, making the Papin genealogy hard to decipher with all the double cousins, etc.

Pappan's Ferry, 1856 by Samuel Reader

Kansas State Historical Society

The Papin brothers took advantage of their right to live on Gonville riverbank land to open a thriving ferry business in the early 1840s. The ferry was a simple operation, a flat boat pulled across the wide, shallow Kansas by ferrymen who propelled the boat by hand.

Papin's Ferry was one of the few ways to cross the Kansas River, geography that brought prosperity as Santa Fe and Oregon Trail traffic across Kansa land increased.

By Henry Worrall

Kansas State Historical Society

The bridge built by the city of Topeka in 1857 put an end to the ferry and in 1865 much of Julie's land was sold. She, Louis and several of their children moved 60 miles southwest to the Kansa reservation. Their eldest Ellen or Helen, born in 1840 and reported to have been schooled at a St. Louis convent had died in 1862. When Ellen was 19 she'd married a divorced white man, Indiana-born Orren Arms Curtis who had come to the Kansas Territory in 1855.

Orren Arms Curtis (1829-1898), known as Jack, a

Captain in the Kansas Volunteers during the Civil War.

Kansas State Historical Society

Jack was married 5 times, divorcing 3 wives. He took no responsibility for the raising of his two children by Ellen. Once orphaned and abandoned they went to live with Ellen's mother Julie Gonville in her Topeka home and then on the Kansa Reservation where Charles attended the Quaker Indian Mission School in the 1860s.

Concrete marker for Ellen Pappan Curtis erected long

after her death

The Block

This original block Kansa Star is a variation of

BlockBase #1243 with added and subtracted seams.

Print the pattern on an 8-1/2" x 11" sheet. Note the square inch for scale.

Kansa Star by Jeanne Arnieri

The Next Generation

When Charles was 13 in 1873 the Kansa were moved to Oklahoma. He recalled that on the advice of his Papin grandmother he decided to remain in Topeka living with Jack Curtis's mother on the south side of the river in the white world. His father returned to sue for a share of Julie Papin's property left to Charles and sister Elizabeth. The Papins and young Curtises won that suit and kept their inheritance.

Charles Curtis (1860-1936) at 18.

Charles spent his adolescence working at odd jobs, such as jockeying race horses and, as he phrased it, learning to be a Methodist and a Republican from his Indiana grandmother. He studied law in the 1870s and entered politics in 1884, elected as district attorney and then U.S. Representative in 1892 at 32. A career in the Senate began in 1907, where he was chosen the first official Majority Leader, a powerful position. In 1928 he announced for the Presidency but Republicans nominated Herbert Hoover, adding Curtis to the ticket as Vice President.

After losing the 1932 election to the Roosevelt/Garner Democrats Charles retired to a Washington law practice, dying suddenly of a heart attack in 1936.

Julie Gonville Papin lived to see grandson Charles elected to the U.S. House of Representatives before she died in 1896, an American star.

Isabelle Papin Auld (1881-1962) with her

great-grandmother Julie about 1890.

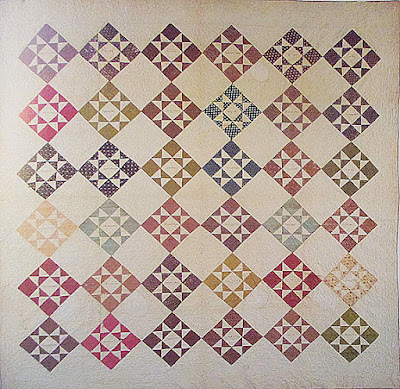

Sugar Loaf quilt (1890-1925) found online, signed J R Papin, said to be from

a branch of the family in St. Genevieve, Missouri.

A dozen Kansa Stars by Becky Brown

Photoshopped together in a repeat pattern.