Woman at a Quilting Bee by Henry Mosler

A nostalgic view in the early 20th century

"I spent most of the day quilting. Occupation is absolutely necessary to keep one sane in these troubled times, but sewing materials, like everything else, have doubled in price --- due to the war."Elizabeth Lindsay Lomax, Baltimore, September 12, 1861.

Elizabeth Lomax's published diary includes several references to quiltmaking. She quilted alone for the most part (we'd guess at her frame) and described quilting rather than piecing or other patchwork. This Civil War description was written while she was a refugee from her home in Washington D.C., spending time in Baltimore, Maryland, which was teetering between Union and Confederate loyalties. Maryland never seceded and Elizabeth took her Southern sympathies home to her Virginia birthplace.

Her granddaughter published selections from the diary of Elizabeth Virginia Lindsay Lomax (1796-1867), beginning with entries in the 1850s as increasingly divisive rhetoric echoed through the nation's capitol. Elizabeth was a widow with 6 grown children and a granddaughter when the Civil War commenced.

The 1860 Census

Son Lundsford Lindsay Lomax was at West Point when the diary began.

After graduation he served in the U.S. Army on the Great Plains before the War.

In a long and forgotten war, US troops fought

Indigenous Floridians between 1816 and 1868.

Her late husband Mann Page Lomax (1787-1842) had died of disease caught while fighting in the Seminole War in Florida. They'd married in 1820 and Elizabeth lived in Massachusetts and Rhode Island while Page, as she called him, was stationed in Florida. Left with many girls and a young son whom she adored, Elizabeth earned a living in several ways.

"Very warm today. Nevertheless I finished my work for the War Department and sent it in." July 20, 1854.

Once the Civil War expanded women's working roles, copyists

and other clerks went to the office every day, but in Elizabeth's

time she worked from home.

She was a copyist of government documents in Washington and spoke often of "writing" at home, a job, a political favor, for genteel women fallen on hard times. She was an excellent musician and in 1854 decided to give harp lessons, but not without some worry about trespassing outside "woman's sphere."

"With my large family my expenses increase daily - After much consideration, I have decided to make use of the talent with which God has blessed me and give lessons on the harp and piano. Would my dear Page be displeased with me for deserting my woman's sphere - the home fireside? On the contrary, I believe that he would understand and approve. " September 19, 1854

She also received a government pension for her father's service in the Revolution and requested additional payments for her husband's death. Her "darling son" also sent her money. She managed to assemble these various incomes into enough capital to build a new house at G Street NW & 19th, a few blocks west of the White House, which they moved into during the Christmas season of 1859.

"Received one hundred dollars for copying today. My Christmas present from Uncle Sam. I am dreaming dreams these days - of building a home of our own - with a garden. If my Revolutionary claim goes through I shall certainly build a house - 'all the King's horses and all the King's men' could not stop me!" December, 1855.

The diary in those five years before the Civil War reveals a rather delightful home, full of pretty women in their 20s, many beaus and many boys, friends of son Lindsay like J.E.B. Stuart and Fitzhugh Lee. But once the war began Elizabeth's Virginia loyalties like the Lee's inspired her to choose the Confederacy.

"Taking the Oath"

Living in federal Washington she was required to take the "oath," a pledge of loyalty to the Union. She refused. Her pension, her copying job and the carefree days were gone. Son Lindsay resigned from the U.S. Army and joined the Confederacy. She and the girls rented out the house, moved to Baltimore and then to Virginia.

"A frightfully exciting day. Riots here and in Baltimore, many persons shot, also a heartrending day for Lindsay and for me. …This evening Lindsay told me that he had sent in his resignation." April 21, 1861

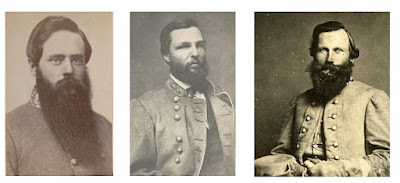

Lindsay Lomax flanked by his Confederate friends Fitz Lee and J.E.B. Stuart.

Lindsay and Fitz survived the war; Jeb did not.

Godey's in 1859 showed a Tarleton dress,

made of a cotton stiffened with starch.

The Lomax daughters whose pre-war lives were full of ruffled Tarleton dresses and yellow roses followed their mother to Baltimore where their Confederate sentiments (and probably some smuggling, etc.) attracted the attention of the city's Union occupiers.

Read Elizabeth's published diary, edited by her granddaughter, another Lindsay Lomax, in the 1940s.

"Papers of Elizabeth Virginia (Lindsay) Lomax (1796-1867) consist of correspondence, 1820-1857; and a ten-volume diary, 1848-1863, kept in Chillicothe, Ohio, Norfolk, Va., Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Md., concerning, in part, her life in Washington and Baltimore during the Civil War."

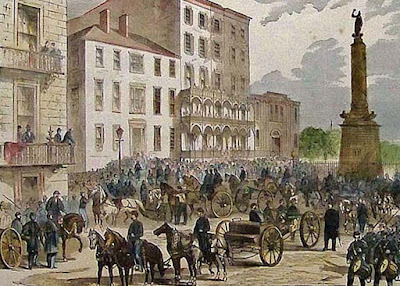

Baltimore's Monument Square under Union occupation

Daughter Virginia Sarah Lomax (1830-1915) and two of her sisters were ordered to leave Baltimore and warned that their return would be punished with treatment as spies. After Lincoln's murder in mid-April, 1865 Virginia ignored the order and found herself imprisoned with suspected conspirator Mary Surratt and other women in Washington's Old Capitol Prison.

Indignant at Yankee suspicions after the Southern plot to kill Union government officials, Virginia published a book full of typical Confederate astonishment that the enemy was lacking in chivalry and manners and prison food was miserable.

After the war, Virginia and her single sisters, twins Julia and Mary Noel, opened a girl's academy in Warrenton, Virginia.

The family built a house large enough for boarders on Culpepper Street ,

which they called Balcarres after an ancestral home in Scotland.

Four sisters are buried together in Warrentown.

1944 Review

And consider that there is a lot more to that journal. The unpublished ten-volume diary from 1848-1863 is located in the Virginia Historical Society. What else did Elizabeth have to say?

https://researchworks.oclc.org/archivegrid/data/709891012

See a post I wrote about the Lomax family 12 years ago:

Read Leaves from an old Washington diary, 1854-1863:

https://www.seekingmyroots.com/members/files/H000895.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment