Antebellum Album #12: A Double Life by Becky Brown

Our last block in the Antebellum Album series

recalls Emily Wharton Sinkler.

Philadelphia's Navy Asylum housed the Naval Academy

In the antebellum period Philadelphia was the center for American education, not only in its elite French Schools for women but also for men's academies and colleges, among them the predecessor of the U.S. Naval Academy. Charles Sinkler of South Carolina attended classes there in 1841 training to be a Midshipman.

Emily Wharton Sinkler (1823-1875)

After his year in Philadelphia he forged a long-term Northern connection, marrying 19-year-old Emily Wharton daughter of a real estate lawyer. Philadelphia snob Sidney George Fisher was not fond of the women in Emily's family. Her mother and older sister "are at the head of the blue school of mawkish, sentimental, would be literary ladies lately got up here. They are more darkly, deeply blue than the rest." By blue he meant well-read and educated.

We can imagine how a couple of attractive and well-bred young people, a naval officer and a Philadelphia belle (if a little blue), may have met and courted.

St. Stephen's Church where Emily married

still stands in Philadelphia.

A Southern planter and a woman descended from Quaker Philadelphia's founders might face conflicts often seen in mixed marriages like the union between actress Fanny Kemble and slave-holder Pierce Butler. By the time of Emily's 1842 marriage the battling Butlers were the talk of Philadelphia.

Butler and Kemble divorced in 1849

Surely someone must have pointed to the Butlers as a cautionary tale before Emily wed and sailed south to live in Orangeburg County on the Santee River.

1911 map with plantation areas in pink and the city of Charleston

at the red arrow. Much of their neighborhood is now under Lakes Moultrie & Marion.

Eutaw, 1939, from the Library of Congress,

a Sinkler cotton plantation where Emily joined the family in 1842.

These Lowcountry plantation homes were not mansions

imagined in movie sets of Tara.

Yet, Emily and Charles's marriage was a success, not only at the personal level but also because it affected so many family members in positive fashion. A prime reason for that success was shared social class. As Daniel Kilbride pointed out in his book An American Aristocracy: Southern Planters in Philadelphia, antebellum families like the Wharton and Sinklers valued membership in an American aristocracy as more important than any North/South cultural differences. Emily would have raised far more eyebrows had she married a middling Philadelphian.

A second factor was Emily's personality. She was no prima donna but a sunny, energetic woman who grew to love her in-laws. A third important contributor was the young Sinklers decision to split their year between two cultures.

Twice a year Emily traveled by ship between her two homes.

Fall trips back to South Carolina during

hurricane season caused much anxiety.

The Sinklers were comfortable in their double life, spending October through March in South Carolina Lowcountry and spring and summer, the sickly season, in Philadelphia. Her parents' Pennsylvania home and later one of their own provided a refuge from Carolina's climate and a cosmopolitan cycle to their antebellum years.

Center of a Carolina Lowcountry white work quilt attributed

to Charlotte Evance Cordes (1767-1826) in

the collection of the D.A.R. Museum

Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, in 1856.

L.J. Levy & Sons is on the corner at left.

Chestnut Street was the place to promenade and Levy's the place to shop.

Emily may have spent many months every year in a rural backwater but she did not lack for civilization's blessings. The Whartons sent Philadelphia newspapers, English magazines, novels---and fabric. She kept up with fashion through Godey's and Peterson's.

Summer trips to Philadelphia included shopping on Chestnut Street. When at the the plantations she often asked her family to purchase fabric at Levy's. In 1848 she wrote sister Mary:

"I enclosed a note asking you to see about some furniture chintz for me....I wish you would inquire the price in Philadelphia and let me know in your next letter. Don't forget this."

Levy's interior could not have been as magnificent as

this lithograph claims but it was the fashionable yard goods store.

In 1852 Mary sent fabric swatches. "The patterns gave me great satisfaction," wrote Emily. At first I guessed she meant dress patterns but I realize she was talking about the print fabrics as patterns.

Charles "was keen for getting four dresses of the sort but I thinking that, rather too much of one good thing, am contented with getting one. Will you therefore get me 10 yards of the blue and [sister-in-law] Anna 10 yards of the brown.....Please get me some patterns of whatever they have pretty at Levy's in the way of Spring and Summer best dresses...."

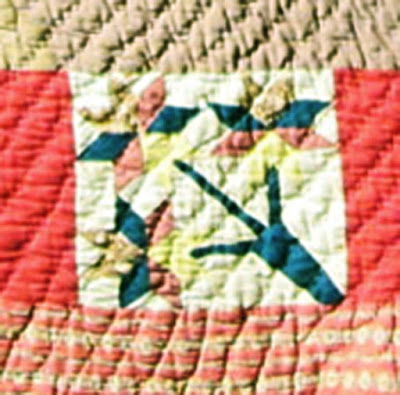

The Block

A Double Life by Mark Lauer

The star inside another star (a good idea) is not that common in antique quilts.

Here's one that looks to be about 1900 from a Quilters Newsletter cover.

BlockBase #2167.

The Ladies' Art Company called it Stars & Squares about 1890;

Ruth Finley Rising Star in 1929.

This album found in the Connecticut project has

Turkey red blocks dated 1847 to 1855, set together with

a gold print.

The double star recalls Emily's two homes and two families.

A Double Life by Pat Styring

Cutting a

12" Finished Block

A - Cut 5 squares 3-1/2".

B - Cut 1 square 7-1/4". Cut into 4 triangles with 2 diagonal

cuts. You need 4 triangles.

C - Cut 4 squares 3-7/8". Cut each in half diagonally to make 2 triangles. You need 8 triangles.

D - Cut 4 squares 2".

E - Cut 1 square 4-1/4". Cut into 4 triangles with 2 diagonal

cuts. You need 4 triangles.

F - Cut 1 square 2-3/8". Cut each in half diagonally to make

2 triangles. You need 8 triangles.

Sewing

A Double Life by Denniele Bohannon

Giant vintage double star medallion

from Laura Fisher's inventory

A Sentiment for December

Here's a 3" wide version of Hannah Dubree's signature

in a music book from a star block in the collection of

the Philadelphia Museum of Art:

During the War & After

Sailing between homes in Philadelphia and Charleston came to an end after the battle of Fort Sumter in Charleston's bay in 1861. Emily and Charles remained in South Carolina throughout the war. With his conflicted loyalties Charles did not enlist but eldest son Wharton Sinkler (1845-1910) joined the South Carolina Cavalry when he was 17.

2nd South Carolina Cavalry in camp

Confederate troops brought slaves to do chores like cooking and laundry. Wharton Sinkler

was accompanied by Mingo Rivers (1829-1880). Both Wharton and Mingo survived the war. Wharton attended medical school at the University of Pennsylvania and remained a Philadelphian for the rest of his life. Mingo returned to South Carolina where he is buried in the plantations' burial grounds. Emily is there too in a cemetery now an island in Lake Marion, which diverted the Santee River and Eutaw Creek and flooded the Sinkler plantations in the 1940s.

A Double Life by Mark Lauer

Emily's descendants have documented her life well. Read her antebellum letters in the book Between North and South: The Letters of Emily Wharton Sinkler, 1842–1865. Edited by Anne Sinkler Whaley LeClercq.

See a preview here:

https://books.google.com/books?id=i1SeQq_M5vYC&printsec=frontcover&dq=emily+wharton+sinkler&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjUps7Q5OvWAhWm14MKHQaxAU8Q6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=emily%20wharton%20sinkler&f=false

And see more about her here:

https://books.google.com/books?id=JKTqCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA20&dq=emily+wharton+sinkler&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjUps7Q5OvWAhWm14MKHQaxAU8Q6AEIPTAE#v=onepage&q=emily%20wharton%20sinkler&f=false

https://books.google.com/books?id=RzUgnbfcH5sC&pg=PA50&dq=emily+wharton+sinkler&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjUps7Q5OvWAhWm14MKHQaxAU8Q6AEIUDAH#v=onepage&q=emily%20wharton%20sinkler&f=false

A Double Life by Denniele Bohannon

We are finished!

12 blocks.

Becky Brown's beautiful top.