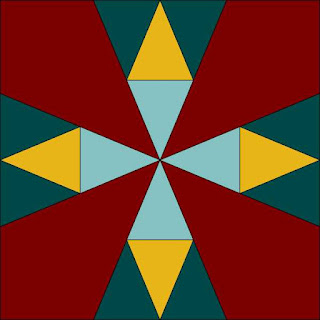

#12 Kaleidoscope Star for the Grimkes by Jeanne Arnieri

The Grimkés became Americans in the early 1730s when brothers Frederick and John Paul Grimké emigrated to Charleston in the colony of South Carolina.

Frederic was born in the German principalities in 1705; Jean Paul Grimké was

born in France in 1713.

John Paul married Mary Faucheraud (1722-1791) and in 1852 their son John Faucheraud Grimké was born. Like many Charleston elite John went north to school at the College of New Jersey in Princeton. He then sailed for England to attend Trinity College at Oxford in England and when he returned to South Carolina became active in the new American independence movement.

College of New Jersey in 1764

Princeton University Collection

John Faucheraud Grimké (1752- 1819) in 1791

By John Trumbull, Yale University Art Gallery

John F. Grimké fought for colonial independence, achieving the rank of Colonel, captured and exchanged after the 1780 Siege of Charleston, one of the rebels' worst defeats. He fought in Savannah in 1779 and Yorktown in 1781. His family's pension application tells us that his widow was awarded an annual pension of $600 from 1836 till her death in 1839. See their application here:

1788, John F. Grimke was the Charleston's Intendant, the mayor.

John F. followed the standard career for a Charleston aristocrat, becoming a politician (mayor and a state legislator in the 1780s, Associate Justice of the state's Court of Common Pleas) and marrying well. In 1784 he wed Mary Moore Smith, daughter of wealthy planters Thomas and Sarah Moore Smith of Berkeley Parish.

Mary Moore Smith Grimke (1764-1839)

Watercolor on ivory in the Gibbes Museum's

Miniature collection was painted by Pierre Henri in 1791.

Between 1785 and 1805 Mary gave birth to 14 children; 11 survived to adulthood. They spent their winters in Charleston in this evolving, enormous house at 321 East Bay Street, purchased in 1803.

The Blake-Grimke house (here the back) has been restored and is now a law office.

Belmont

And their summers at Belmont, a plantation up by Spartanburg in Union County, waited on by enslaved servants. Louise W. Knight lists 17 in 1819:

- Nancy, elderly and "useless"

- Will, ditto

- Rhina, “plain cook, washer, ironer,”

- George “coachman & shoemaker,”

- Sam, "coachman,”

- John, house servant,”

- Prince, "house servant in training"

- Bess, ladies' maid with 4 young children

- Maria, ladies maid and seamstress

- Margaret, ladies maid and seamstress

- Peggy, "plain washer and ironer,”

- Dick, “plain cook.”

The Grimké family lived in the Heyward-Washington House,

now owned by the Charleston Museum,

when Sarah was young.

Mary Smith Grimke was not one of those "beloved mistresses" of nostalgic memory. Her daughters recalled her violent dealings with the slaves whom she had beaten often. She struck them herself when in a temper. Her second eldest daughter Sarah Moore Grimke, rather traumatized by this home life, despaired of spiritual sustenance. When her father John Faucheraud Grimke became mysteriously ill in 1819 Sarah in her late 20s accompanied him to Philadelphia for medical advice.

Sarah Moore Grimke (1792-1873) adopted Quaker garb

There Sarah encountered Quakerism, finding antislavery sympathy and religious direction that changed her life. Her father was told to seek sea air and they moved to a boarding house by the Atlantic in Long Branch, New Jersey where John died in August. Sarah returned to her unhappy home life in Charleston, her main joy sister Angelina 13 years her junior. Angelina looked up to Sarah and followed her into the Quaker faith and abolitionism.

Angelina Emily Grimke (1805-1876)

William L. Clements Library Collection

University of Michigan

Kaleidoscope Star by Denniele Bohannon

These rebellious sisters who became Quakers and moved north were quite influential in the American antislavery circuit of speakers and authors. Brother Henry (1801-1852) was rebellious in more conventional southern male fashion. After first wife Selina Simmons Grimke died in 1843 he began a domestic relationship with enslaved Nancy Weston (1810-1895) with whom he fathered three sons: Archibald in 1849, Francis in 1850 and John born in 1852 after Henry's death in a typhoid epidemic.

Archibald, Francis and John Grimke

took their father's name.

Henry did not free Nancy or his sons (possibly because it was illegal) but willed them to white son Edward Montague Grimke, who treated his half brothers as slaves as did Sarah and Angelina's sisters Eliza & Mary Grimke, single women who lived with nephew Montague in Charleston, according to the 1860 census.

The census's 1860 slave schedule lists 4 young people

living at the Grimke home; none of the boys are the right ages for

Nancy's sons but ages for these unnamed people were not accurate.

The boys also may have been living with their mother in the city.

Family Search

In 1853 daughter Eliza had sold 4 people from brother Henry's estate: Jacob, Charlotte, Jean and Doe to William H. Houston for $2,120.

.

January, 1853, Henry's estate sells 33 people.

An undistinguished Grimke, Montague's 1896 obituary tells us

he was wealthy, Christian and had many friends (Grimkes in

the North not among them.)

Sarah & Angelina, photos from the Civil War years

Henry's family kept the information about his second family secret from his abolitionist sisters. (Was anyone communicating with the notorious Sarah and Angelina?) But in 1868 Angelina read about an outstanding student named Grimke at Philadelphia's Lincoln University, a school for Black men. Discovering their nephews, the women helped with their college expenses. Archibald graduated from Harvard Law School, Francis from Princeton, both becoming Grimkes distinguished in diplomacy, the N.A.A.C.P. and the Presbyterian church.

Francis married Charlotte Forten, of another family of American stars, and lived in Washington D.C where he was minister at the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church. Their only daughter died as an infant but they helped raise brother Archibald's daughter Angelina Weld Grimke (named for her aunt Angelina Grimke Weld) who spent her adolescence with her uncle and aunt while her father was minister to the Dominican Republic, then Santo Domingo.

The Block

Kaleidoscope Star is an original block, designed for the

fractured picture of the Grimkes.

The block, a form of Maltese Cross is adapted from the patterns in BlockBase's 2700s.

Print the pattern on an 8-1/2" x 11" sheet. Note the square inch for scale.

Kaleidoscope Star by Becky Brown

Later Generations

Angelina Weld Grimke (1880-1958)

The younger Angelina was raised by her father, Aunt Charlotte & Uncle Francis.

Angelina was not a star in her own time but she has lately become one for the poetry, stories and plays she wrote and published while she was teaching in Washington. Her themes: The Black past and the frustrations of Lesbianism in a bigoted time.

Denniele's plan

John Grimke Drayton (1816-1891)

And just one more star Grimke: American horticulturalist John Grimke Drayton, son of Thomas Smith Grimke, grandson of John Faucheraud and Mary Smith Grimke. Thomas Smith Grimke made a profitable marriage to South Carolina aristocrat Sarah Drayton whose family came from Barbados to establish the huge Magnolia Plantation along the Ashley River.

Magnolia in 1853

Alas, Sarah produced no sons. Rather than losing the Drayton name her father willed the land to his Grimke offspring on the condition they change their name to Drayton---the Grimke-Draytons. John Grimke Drayton inherited Magnolia in the 1840s becoming a gardener of note.

Among the innovations he and his African-American crew introduced: A fashion for naturalistic gardens rather than formal English and French arrangements. They raised numerous species of camellias and azaleas, popularizing them in the United States.

After the Civil War Drayton opened the gardens to the paying public,

an innovation born out of financial desperation. Magnolia Plantation

enjoys the reputation as the oldest public garden in the U.S.

Jeanne Arnieri's top

Jeanne's block #12 Photoshopped as an all-over design

And we are finished with American Stars.

American Stars by Becky Brown and the Country School Quilters,

made for a veteran.

And here are three more simple sets.

More finishes soon.

Read Louise Knight's posts on the Grimkes:

See a post about Charlotte Forten Grimke here:

A new book by Kerri K. Greenidge is "a revisionist history of a pair of white abolitionist sisters," according to the New York Times. See a preview of The Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family.

Thanks Barbara, as always!

ReplyDeleteWow, what a family story and such a great quilt! Thanks.

ReplyDeleteReaders may also enjoy Sue Monk Kidd's book "The Invention of Wings" which is a fictional story based loosely on the Grimke's.

ReplyDelete