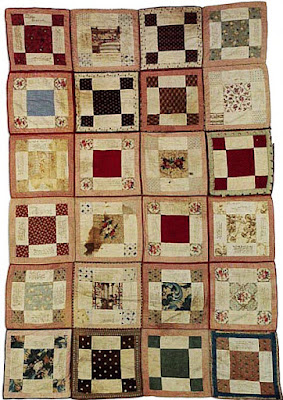

Collection Rochester Historical Association, New York

Pre-quilted & bound block from a Sanitary Commission quilt

associated with Cornelia Loring's family,

pictured in Pamela Weeks's & Don Beld's Civil War Quilts (revised.)

"My grandmother, Mrs. Charles G. Loring worked in the [Sanitary] Commission rooms in Boston by day, in the evening she would bring materials and drive about in her buggy to distribute them among the neighbors, collecting the finished garments to be carried back to Boston by an early train."---Katharine P. Loring recollections of her [step] grandmother Cornelia Amory Goddard Loring's work during the Civil War.

Katharine Peabody Loring (1849-1943)

Katharine's father's mother Anna Pierce Brace Loring had died in 1836 so Cornelia was the grandmother she knew. Less than a year old when grandfather Charles Greeley Loring married his third wife, Katharine was an adolescent during the Civil War and may have been recalling her grandparents summering at the sea shore in Pride's Crossing where train service was available for the 30 mile commute to Boston.

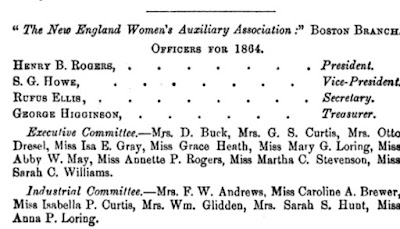

Cornelia Loring (1810-1875) seems to have been a one-woman supply chain for textiles funneled to & from the shore to the "Industrial Committee" of the New England Women's Auxiliary Association.

"The Industrial Committee, chaired by Mrs. Frank W. Andrews, oversaw the making of clothing and bedding for soldiers and hospitals. It provided patterns and fabric for distribution to sewing circles and soldiers aid societies throughout New England, and to women in need whose work was paid for by benefactors."

Sewing machine, 1865

In 1863 the women of greater Massachusetts donated 5,400 quilts

to the cause.

Collection Rochester Historical Association, New York

56" x 84", Dated 1864-1865

This narrow quilt appears to have been stitched

to warm a hospitalized soldier towards the end of the war.

The nine-patch probably survived because it was never shipped.

Pamela Weeks in the recent revision of her book Civil War Quilts concludes Cornelia's stepdaughter Susan Loring Jackson may have organized its making. Inscriptions include Susan's name and two of her children's with locations in Beverly Farms, adjacent to Pride's Crossing .

C.G. Loring owns beachfront property in this 1872 map

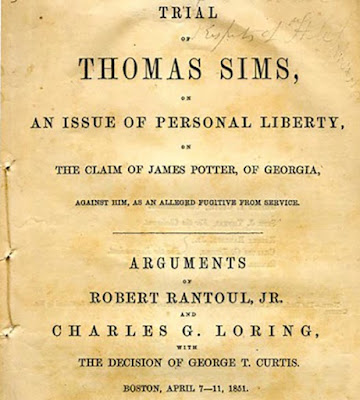

Wendell Phillips speaking for Thomas Sims, 1851

Gleason's Pictorial Drawing Room Companion

Lorings were so numerous in Massachusetts that Charles's double first cousin Edward Greely Loring was the judge who ruled against Sims and sent him back to Georgia.

Picture from Pamela Weeks's Civil War Quilts

Detail of the Loring quilt with a war-time print of soldier and cannon.

Library of Congress

Mount Vernon Street in the 1850s with a view of Bunker Hill

Cornelia's stepson Charles Greeley Loring II had a distinguished army career.

Major-General Charles Greeley Loring (1828-1902)

Ninth Army Corps

Grandson Lt. Patrick Tracy Jackson III

5th Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment

Ednah Dow Cheney in a biography of Abby May recalled the Auxiliary's origins in December, 1861 after national Sanitary Commission officer Frederick Law Olmstead issued a call for local soldiers' aid organizations under the Commission's canopy:

Samuel Howe, at first the lone actor in gathering and dispensing supplies, had experience raising money, clothing and bedding for anti-slavery causes such as Kansas settlers fighting for a free-state constitution so he looked a good choice to administer a similar project. But as Cheney noted he was "inclined to think it was not worth while...to organize work of the women...," attitude quite consistent with Howe's misogynistic reputation. (See Elaine Showalter's, The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe for a portrait of his unhappy marriage trying to repress his wife's independent activities.)

The civil war's "cruel fangs fastened upon the very heart of Boston, and took from us our best and bravest.... The work of the women in providing comforts for the soldiers was unremitting. In organizing and conducting the great bazaars, which were held in furtherance of this object, many of these women found a new scope for their activities, and developed abilities hitherto unsuspected by themselves."Julia Ward Howe, Reminiscences, 1899

The Sanitary Commission and its local branches were run by men with women deputized to conduct most of the raising of supplies (after all, women could not make contracts, etc.)

Efficient branches of the Sanitary Commission seemed to benefit from smooth relations between the men "in charge" and the female committees. But the Boston association had problems with dissension, perhaps indicated by its name as an Auxiliary. Like other regional groups Bostonians put on a fund-raising fair during the latter years of the war despite "the Executive" (one or more of the men?) discouraging the idea.

Abby Williams May (1829-1888), first cousin to

Abby May Alcott (Marmee in Little Women), was Secretary of the Boston group.

Note the Lorings

Elevating the items for sale in Boston above the "usual variety of fancy and useful articles" were displays of fine arts remembered by twelve-year-old Sarah Gooll Putnam (1851-1912) who was related to the Lorings through aunt Mary Ann Putnam Loring (Charles Greely Loring's middle wife.) Sally recorded her impressions of the event, an account found online.

Cornelia Loring ran the Boston table, offering fine

art and useful articles.

Boston Music Hall, 1850s, Massachusetts Historical Society

Abby May's cousin Louisa May Alcott dramatized "Six Scenes from Dickens" but complained, “Things did not go well for want of a good manager and more time. Our night was not at all satisfactory to us, owing to the falling through of several scenes for want of actors [but] People liked what there was of it.”

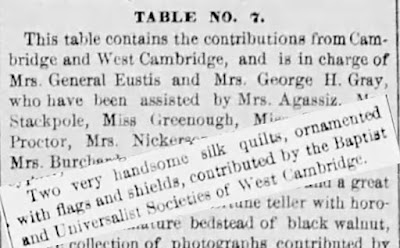

Two patriotic silk quilts at Table #7 from the women in Cambridge.

As might be expected Cornelia and her husband were in favor of Abraham Lincoln's re-election in 1864. Diarist Regina Shober Gray recalled the torch-light parade held on election eve, which she watched from Cornelia and Charles's windows on Mount Vernon Street. "It was a beautiful sight....Mrs. Loring’s party...was not so crowded as I supposed, but was a very pleasant gathering; no doubt many declined her invitation, on acct. of the torch–light."

Boston Globe Obituary

Picture from Pamela Weeks's Civil War Quilts

Many of the surviving Sanitary Commission quilts were made

in New England using their rather unusual "pot-holder"

method of binding each block before joining them.

Further Reading:

See more about Cambridge women's work for soldiers' aid at this post about the Banks Brigade that met at the home of another of Cornelia's stepdaughters Jane Loring Gray.

Pamela Weeks & Don Beld, Civil War Quilts: Revised, Updated, and Expanded. 2020

Preview: https://www.amazon.com/Civil-War-Quilts-Revised-Expanded-dp-076435888X/dp/076435888X/ref=dp_ob_title_bk?asin=076435888X&revisionId=&format=4&depth=1

https://www.masshist.org/collection-guides/view/fa0506

Preview: https://www.amazon.com/Civil-War-Quilts-Revised-Expanded-dp-076435888X/dp/076435888X/ref=dp_ob_title_bk?asin=076435888X&revisionId=&format=4&depth=1

Judith Ann Geisberg, Civil War Sisterhood: The U.S. Sanitary Commission and Women's Politics

Elaine Showalter, The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe

Massachusetts Historical Society: New England Women's Auxiliary Association Recordshttps://www.masshist.org/collection-guides/view/fa0506

These posts are always so interesting. And I love seeing the fabrics.

ReplyDeleteThank you for post including Hetty Reckless …. I am researching to do writing about her life in both fiction and non fiction .

ReplyDelete