Wednesday, October 30, 2024

Kentucky Classic #8: Whig Rose for Henry Clay

Wednesday, October 23, 2024

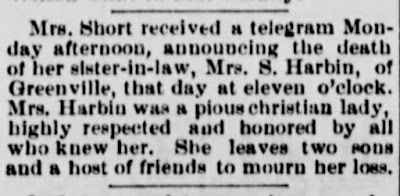

Susan Short Harbin's Civil War

When the Civil War began Susan was a widow, husband William having died in 1858, preceded by son David who died at one. The 1860 census lists her at 35 as a “Domestic,” with $6,000 in property (the house?) and children Jane, George and Joseph, all under ten, living with her plus Marcella, a 20-year-old and Elizabeth, a 55 "domestic."

Like most 19th-century women Susan left little in the way of a paper trail. She did not remarry.

Did Susan Harbin stitch this example of one of Kentucky's few surviving chintz-style quilts?

See more about the style here:

http://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2020/05/sarah-millers-quilt-how-to-make-tree-of.html

And see two recent posts on the lack of early Kentucky quilts here:

http://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2024/10/kentuckys-earliest-quilts-2-missing.html

http://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2024/10/kentuckys-earliest-quilts.html

Wednesday, October 16, 2024

Cornelia Grinnell Willis's Civil War

When Civil War commenced in 1861 Cornelia Willis had been married to successful newspaper publisher Nathaniel Parker Willis for about 14 years.

Cornelia was Willis's second wife marrying him when she was about 22. She met him in Washington where she lived with her adoptive parents U.S. Representative Joseph Grinnell (her father's brother) and Sarah Russell Grinnell (her mother's sister.) A complicated family here of double aunts and double uncles....

Cornelia became stepmother to Nathaniel's four-year-old daughter Imogen, whose mother Mary Stace Willis had died in childbirth along with her second baby, much to the sorrow of the families and Imogen's nursemaid, Harriet Jacobs.

By 1861 Cornelia had four living children of her own. Her last child was a daughter born in the fall of 1860 who died at birth. They were living in Cornwall, New York, 40 miles up the Hudson from New York City in a 14-room house they built called Idlewild.

"He was, of course, a Union man. But he retained a secret sympathy with the South, and a liking for 'those chivalrous, polysyllabic Southerners, incapable of a short word or a mean action,' whom he had known at Saratoga years before.... the [newspaper's readers], a large proportion of whose subscribers were in the South, had fallen off seriously."

Cornelia remained at Idlewild when war began with her children but income was tight and she rented out her mansion, returning to live with her father at New Bedford. In 1863 she reclaimed the house, turning it into a girls' school. By then Nathaniel lived in New York, refusing to visit his family and home in reduced circumstances. His health was failing (suffering from seizures among other crises.) He died on his 61st birthday in 1867 at Idlewild.

The Willis women and children remained quite close to Harriet and her daughter Louisa, who was in boarding school before the Civil War. Tracing their histories one can see lives intertwined throughout the 19th century and into the 20th.

"We do all the computing connected with the meridian circle, our special work being to locate the position of certain stars…Harvard is the only college that employs women as mathematical computers." Imogen.

Wednesday, October 9, 2024

Washington Whirlwind #10: President's Block

Her long-expressed refrain that no one suffered more than she was just a prelude to the disaster that would have traumatized anybody. Her dying husband was moved to a boarding house bedroom across the street from the theater where he was shot. The Petersen House at 516 East 10th Street became the site of an overnight death watch.

the situation was hopeless. His father recorded in his journal: "When Chas reached the Box the President was lying upon the floor. Water and stimulants were used immediately but without avail in attempts to revive him."

"The giant sufferer lay extended diagonally across the bed, which was not long enough for him. He had been stripped of his clothes. His large arms, which were occasionally exposed, were of a size which one would scarce have expected from his spare appearance. His slow, full respiration lifted the clothes with each breath that he took. His features were calm and striking. I had never seen them appear to better advantage than for the first hour, perhaps, that I was there."